A look at big snowstorms in Colorado’s past:

_ November 2004: A storm that dumps nearly 3 feet of snow in western Colorado contributes to a jet crash at the Montrose airport that kills three, including the youngest son of NBC Sports President Dick Ebersol.

_ March 2003: The most costly storm in the state’s history dumps up to 11 feet of snow and is blamed for at least six deaths in Colorado and Wyoming. Insurance claims reached about $100 million.

_ March 1998: Snow is blamed for a 30-vehicle pileup on Interstate 25 at Monument near Colorado Springs.

_ October 1997: A storm drops 3 feet of snow on the Eastern Plains and 4 feet in Colorado Springs and is blamed for 10 deaths. About 30,000 head of livestock die.

_ February 1995: A storm brings about 20 inches of snow to Silverton and forces six mountain passes to close. An avalanche at Crested Butte damages several condominiums.

_ December 1982: Two feet of snow fall in 24 hours in Denver, paralyzing the city. Main streets remain impassable for days. Critics of then-Mayor Bill McNichols say the city’s response to the storm ended his political career.

_ December 1967: Near-record snow in southwestern Colorado and neighboring states leaves drifts up to 20 feet high. Snow vehicles and airlifts take food to isolated families and livestock.

_ January 1949: A storm blankets Colorado and neighboring states with up to 3 feet. Seven deaths are reported in Colorado.

_ April 1921: A storm dumps more than 6 feet of snow at Silver Lake in 24 hours, a national record for amount of snow in one day.

NATURAL DISASTERS IN THE SAN JUANS

The following text Courtesy of Center of Southwest Studies,

Fort Lewis College

The Center of Southwest Studies, Fort Lewis College

TCP=Traditional Cultural Properties

Fires, floods and avalanches characterize natural phenomena in the area. The Lime Creek Burn, which was the largest wildfire in Colorado history until 2002, covered 26,000 acres of land located between Cascade Creek and Grand Turk Mountain. Although the area burned in 1879, the sparse timber and scarring is still evident. In 1940, over 27,000 Englemann spruce seedlings were planted, resulting in the linear alignment of timber that is visible today. At over 10,000 feet in elevation, the sparse landscape has yet to return to its “pre-fire” condition and remains a testament to the devastation of more than 120 years ago.

A Forest Ranger with compass and canteen plots a fire in the distance. One assumes he runs down the mountain and reports, a far cry from today’s radios and phones.

A Forest Ranger with compass and canteen plots a fire in the distance. One assumes he runs down the mountain and reports, a far cry from today’s radios and phones.

There has been much speculation over whether this fire was a natural event or a last act of desperation by the Utes in resistance to the white incursion into their country. Allen Nossaman provides a thorough discussion of the various points of view in Many More Mountains, Volume 2, pages 258-265, and supports the currently held theory that it is more likely that this fire was a natural event, precipitated by an extremely dry spring. The timing of this fire prior to the Meeker Massacre caused a reaction in southern Colorado that bolstered funding and troops at Fort Lewis and relocated the fort to the more strategic La Plata drainage location.

In contrast to the parched conditions related to the Lime Creek Burn, the summer and fall of 1911 saw one of the wettest and most disastrous seasons in history. Heavy rains saturated the grounds until early October when the San Juan, Dolores and Animas River drainages all flooded. Pagosa Springs, Dolores, Rico, Durango, Silverton, Mancos and every other settlement located near a river in Southwestern Colorado suffered massive devastation from flooding that fall. Every town has its own story of the effects of this flood, which triggered extensive rebuilding.

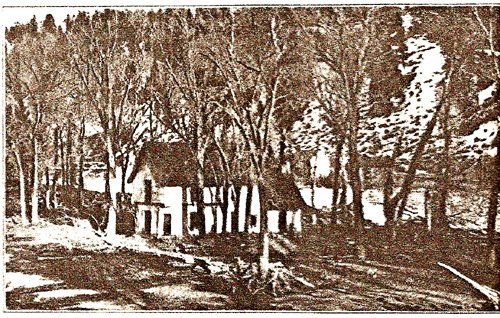

During 1911 Pagosa Springs was damaged by a flood. This house was floated from Hermosa Street down river and lodged in the cottonwood trees in Town Park.

During 1911 Pagosa Springs was damaged by a flood. This house was floated from Hermosa Street down river and lodged in the cottonwood trees in Town Park.

In the high country that feeds the rivers, the San Juan Country has three key ingredients leading to high avalanche probability. Climates with broad fluctuations in temperatures, steep slopes, and high winds combine in the San Juans and the La Platas to create potential avalanche hazards. Modern travelers see the latest attempts to live with avalanches in the snow sheds built on Wolf Creek Pass and Red Mountain Pass. Early settlers and miners had much less protection, and had to adapt their activities to mother nature as much as they could. All mining histories of this region are filled with stories of deaths from avalanches. More research is necessary to determine which of the slide paths hold historical and ethnic cultural meaning, but the Riverside slide path between Silverton and Ouray is a likely TCP candidate. The slide has killed recent Colorado Department of Transportation snowplow drivers as well as travelers from 100 years ago.

Case Study: Avalanche Paths and “The White Death”

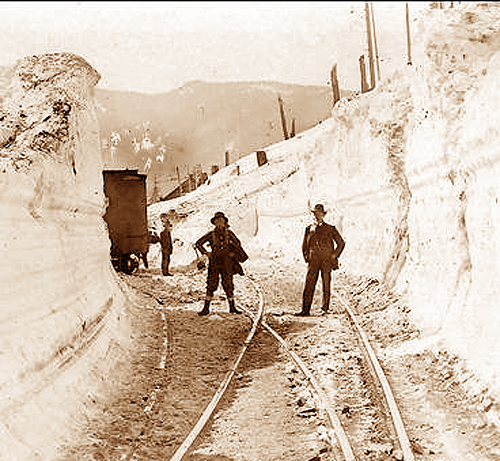

The Utes sensibly stayed out of the high mountains after the first snows of winter, but Anglo explorers coming into the country up Lime Creek and over Stony Pass learned to stay and build cabins despite the deep snows. By the 1880s as San Juan mining became more feasible with the arrival of the railroad into Silverton, gold and silver mining became a year around proposition. In the winter getting out of the mines and into town often meant life or death challenges with avalanches. The history of the San Juans is the history of struggle and survival with the elements, and there are countless tales of death due to winter weather, poor decisions, and accidents on snow-covered slopes. For both previous and current generations of San Juan residents there are tales of winter survival and ingenious methods of negotiating treacherous avalanche paths.

In his classic book on Southwest Colorado titled One Man’s West, David Lavender writes about working at the Camp Bird Mine and how in the 1930s “In wintertime the continual passage of the mules keeps a narrow ribbon of snow packed hard and firm, but to either side of this path is a soft, almost bottomless white morass.” He describes winter snows 35 feet deep and packers who placed blazes on trees. The trail blazes could not be seen at deep snow depths so packers “marked their route by tying rags to the tips of branches which at the time were within arm’s reach.” Lavender describes the confusion of summer tourists who could not imagine how fluttering bits of colored cloth got so high up on the pine trees.

The San Juans represent some of the highest mountains in the Rocky Mountain cordillera. Colorado has more 14,000-foot peaks than any other state, and the highest concentration of 13,000 foot peaks are in the San Juan Mountain range. Navigating through the mountain valleys and gulches in deep snow, especially in late winter and early spring, challenged many a miner. Lavender writes in One Man’s West, “Down the slope we’d just quit pounded the avalanche. A cloud of powdered snow rose hundreds of feet above it. Through the reverberations we could hear the air popping like a giant whip as it rushed in to fill the vacuum left by the slides.” He adds, “A wall of air surged ahead, booming like thunder from cliff to cliff.”

The San Juans represent some of the highest mountains in the Rocky Mountain cordillera. Colorado has more 14,000-foot peaks than any other state, and the highest concentration of 13,000 foot peaks are in the San Juan Mountain range. Navigating through the mountain valleys and gulches in deep snow, especially in late winter and early spring, challenged many a miner. Lavender writes in One Man’s West, “Down the slope we’d just quit pounded the avalanche. A cloud of powdered snow rose hundreds of feet above it. Through the reverberations we could hear the air popping like a giant whip as it rushed in to fill the vacuum left by the slides.” He adds, “A wall of air surged ahead, booming like thunder from cliff to cliff.”

From Cascade Creek to Ouray are more avalanche runs than anywhere else in the United States. Over 100 runs exist and 60 cross U.S. Highway 550 as it moves north over Coal Bank Pass, Molas Pass, and then Red Mountain. Named avalanches along that route have claimed miners on foot, travelers in wagons, and even whole towns like Chattanooga. There are photographs, folk tales, accurate historical accounts, and markers left to commemorate the dead. A few of these avalanche paths qualify as traditional cultural properties because of the way they have been marked. The East Riverside avalanche path contains highway monuments for two snowplow drivers and a minister and his daughters who died within the last 25 years. Earlier deaths are also noted both in books by John Marshall and Jerry Roberts Living and Dying in Avalanche Country, and John W. Jenkins’ Colorado Avalanche Disasters.

Jenkins describes an 1898 avalanche that descended 5,000 vertical feet in a run that extended four and a half miles with a wall of snow moving 225 miles per hour. Because traditional cultural properties link people to place, and because nowhere in the nation are there as many avalanches as in the San Juan Mountains, then the historic and contemporary responses to “the White Death,” represent TCPs erected by ongoing mountain communities. Most TCPs are specific to ethnic groups like Native Americans, but in the high altitude San Juans avalanches have resulted in specific responses to the landscape such as triangle-shaped stone diversion structures intended to deflect avalanches like those up Arrastra Gulch, and even living diversions such as the thick stands of pine trees planted just to the north of the Christ of the Mines Shrine at Silverton.

The slides have names like Henry Brown, Swamp, King Mine, Peacock, Battleship, the Brooklyn Group, Muleshoe, Telescope, Porcupine and Eagle. Avalanche runs have been christened Rock Wall, Snowflake, Wagon Box, Blue Point, Slippery Jim and Mother Cline. Hundreds of miners had to traverse the mountains even when “the avalanches were running on every hand.” Slides took out boardinghouses, tent houses and men walking to work on trails. Immediately search crews would begin to look for their friends trapped in the deep snow. Some were found and dug out immediately, and others were not found until spring, dead, at the bottom of gullies.

A powder cloud traveling at a moderate avalanche speed of 60 miles per hour because of snow crystals would have the same force as a 180 mile per hour wind, and the impact force of the snow can be 30-50 tons per square yard destroying everything in its path. That’s why avalanche deaths are commemorated, and that’s why avalanche paths sometimes have memorials near them. Future TCP research in the San Juans should include the human response to avalanche fatalities at specific sites and the commemoration of other winter deaths in the San Juans by markers and monuments. In New Mexico roadside crosses are considered by the State Historic Preservation Office to be TCPs, and here in southwest Colorado there are also markers near avalanche paths that should be identified, inventoried and protected as cultural resources.