This interview was conducted in 2007 for publication in the local family magazine published by Cory Warden, “The B.R.A.T.”

Remembering the Country Schools of Archuleta County

By Blue Lindner

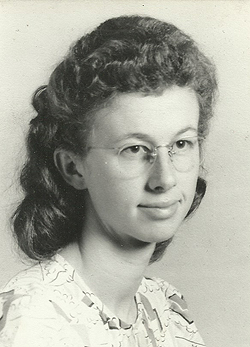

Before 1950, any child living in rural Archuleta County home schooled or attended one of several “country schools” speckled throughout the countryside. Lately I’ve been interested in the concept of the one-room-school house, so I asked Mrs. Elaine Nossaman, a former teacher, if she would be willing to talk about her experiences in that setting.

Elaine Nossaman had a long and varied teaching career in Archuleta County and New Mexico. Her first teaching job was during WWII at a country school in Arboles—a school that is now under Navajo Lake. From there she went on to teach at the Bayles country school, located on County Road 139, which she also attended as a child. From there she went on to teach in Pagosa Springs and Dulce until 1986, when she retired at the age of 60.

E.N.: My name is Elaine Nossaman. My dad was Charles Johnson and my mother was Elizabeth King Johnson. They married on June 22nd of 1920. My sister Genevieve was born in 1921. I was born in April of 1926. My younger sister Charlotte was born in December of 1932, and Marilyn in January of 1935. I’ve lived all my life up till now in Archuleta County. I haven’t lived here all my life because I’m not dead yet. I was born out on my father’s homestead. Dr. Mary Fisher was my mother’s doctor. I went to school in the old Bayles School Building. I started in 1932 when I was six years old. I went my first eight grades in the country school. It was called Bayles School District 16.

B.L.: Is that the little schoolhouse you can see from Highway 160 by the Astraddle-a-Saddle sign?

E.N.: Yes. It’s been moved from where it used to sit around up on the hill. That land was sold and I didn’t want the school to go with the land so I got it moved down into the field. It was on the old railroad grade. The branch railroad line came up from Pagosa Junction. My dad bought the land from Riley Hill in 1936. The Hills ran a saw mill up where part of Parelli’s land is now. My dad bought that place the year they took the railroad out because the Rio Grande Motor Way was bringing freight trucks which carried freight over Wolf Creek Pass. It seemed to be easier to haul freight on the trucks than on the train. I remember before I was old enough to go to school, the teacher boarded with my parents. That was the winter of the big snow. It was over five feet deep that winter. My mama said it started snowing on Thanksgiving Day and snowed every other day all winter. Daddy kept the road open and got the teacher down to the school house. He had an A-frame drag pulled by horses. The teacher rode on the back behind him on a plank. The next winter my little sister was born. While my mother and I were in town for that, the teacher lived in the school house. It was nice when the kids came to school because the building would be warm from the fire she built in the night and early morning. I remember going down in the morning and building fires when I taught there. Sometimes the water bucket would freeze. We’d carry water from the neighbor’s spring over on the other side of the hill to the east. The kids enjoyed going after water because they got out of school for a little bit. We didn’t have faucets and running water or indoor plumbing. We had an outhouse out back. Two of them: one for the girls and one for the boys.

The winter that we went to Pagosa for my little sister’s birth, I missed a month or more of school. When we returned home I got a little bit more school but the district was poor. It was during the Depression and they had to close the school early in March or April. So I didn’t get a whole lot of schooling that year. Then the next year when I started in the second grade there was another little girl named Helen in the third grade and the teacher thought I could keep up with Helen. I did the second grade work until Christmas, and after that she put me in the third grade with this other girl. So I made it through in seven years instead of eight. You can’t do that these days in the public school the way it’s set up.

BPL: How many grandchildren do you have?

EN: I have five grandchildren. My daughter Cindy has three children: Lara, Eddie, and Raymond, who has two children of his own. Then I have two other granddaughters by my daughter, Susan: Lauren and Lizzie. When Susan was a little girl, she liked to take my old sewing spools after I used up all the thread, and she’d nail them on a board. Then she’d take rubber bands and string them on the spool. I’d say, “What is that?” and she’d say, “I’m making a machine.” I’d say “Okay go ahead, that saves me from having to buy toys for you.” So when she grew up she became a bio-med person and now she fixes the machines at Mercy Medical Center whenever they break down. She went to school in Dulce. When I went to Dulce to teach I took my two girls down there with me. Susan went on to Kemper Military School one year. Then she went to school in Fort Collins and got her bio-med degree.

Teaching runs in my family. My mother was a teacher. I had three sisters, and all four of us girls taught school for part of our lives. My sister-in-law was also a teacher. I taught the longest. I have my retirement money and my social security money and it’s almost enough to live on.

In Dulce I was first given a pre-school class with children who needed a little more time to learn to speak English. I had been trained in Alamosa in early childhood education. Then the kindergarten teacher got sick and couldn’t go back. The principal, Mrs. Chon LaBrier, asked if I would take the kindergarten class. I taught kindergarten for 15 years, with about 19 years in Dulce all together. When I retired, they were all sorry to see me leave. After I came back up to Pagosa, I did some tutoring. When I tutored I didn’t really do much. I would listen to them read and if they were having trouble then I would read a page and then they would, back and forth like that. I’ve heard that if you read a book to a child that is at the next grade level, they can comprehend above what their ability to read is, so I think just reading to a child whets their appetite to read themselves. The parents would tell me what I good tutor I was, but I would say “I didn’t do anything except listen to them read. They would catch on and move ahead.” They were also good company to me for about an hour.

B.L.: Tell me about the country school in Arboles.

E.N.: That was my first teaching job. I graduated from Durango High School in 1943. The county school district had to pay for the kids to go to high school in Pagosa but they didn’t have enough budgeted to send the country school kids, so my sister went to Farmington High School. She stayed with my aunt and would help my aunt with her little ones. When I was old enough to go to high school my parents sent me to Farmington, too. My first year in Farmington my grandmother went down with me and rented an apartment and I stayed with her. After that first year I lived there for two years with Curtis and Francis Smith who had two children. Mr. Smith and his brother ran the San Juan Drug Store in Farmington. I would baby sit for them and worked for my room and board. At first she paid me fifty cents a week because I did a good job. Then when we got into the war prices started going up and she couldn’t afford to pay me fifty cents a week. I remember saving my fifty cent pieces. I think I had three dollars worth and I bought myself a pair of shoes at Penny’s. So I don’t know if she thought I was rich because I bought myself a pair of shoes or what but pretty soon after that I didn’t receive any more money. Then in my fourth year my sister Genevieve thought it would be nice if I went to school in Durango. I would be closer to home and I lived with four girls in an apartment in Durango. I stayed there until I graduated. They had a college day where seniors were taken out to Fort Lewis which was in the country at the time, below Hesperus. At that time it was a branch of the Fort Collins College, CSU. It was an agricultural school. We could work in the kitchen for our meals and board, so I did that out of high school. It was called an experiment station. I went one year and intended to go back. We got out of school at the end of April. I came home and I worked for my uncle in the post office. At that time the post office was in the Pagosa Hotel building. The county superintendent came in one day to buy stamps or something and she said, “We need teachers. Our good teachers are going off to the airplane factories where they can make more money. If you will take a test for an emergency certificate, you can teach.” My mother and I caught a bus to the Alamosa County Courthouse and I took the test, and passed. It was a weird test and I wasn’t sure if I would pass it or not, but they said not to worry because everyone passes it, and I passed it. The bus home left very early in the morning, before light. I remember coming over Wolf Creek Pass at the summit just at sunrise and I thought “Oh, this is so beautiful. Early in the morning is the best time of day. People ought to start the day with the sun.” And I guess I got that in my bones because I still like to get up early.

There were two schools that needed a teacher. One was down in Arboles and one was at the Dyke school about four miles west of home in Pagosa. An elderly lady named Susy Ford had first choice and she chose the closer school. That left me with the school in Arboles. My dad took me down there and I was supposed to live in the school house. There was a cook stove and a bed. I didn’t like it. I was there all by myself and I didn’t know the people and I felt awful. There was a couple named Milton and Bessie Seibel who invited me to come up and board with them so I did. When I was in the school house this young man named Royal Nossaman came and picked me up one time. Then Royal would come and get me and the Seibel’s little boy, Donald, pretty regularly and take us to the Seibel’s house. Mrs. Seibel was a hospitable, good person and the best cook, so Royal would stay and eat supper. Sometimes he wouldn’t go home as early as he should have I guess.

Then in the winter he got his call to go to Denver for his physical exam for the army. He never did have to go because the war ended that summer. So we decided to get married in the end of August in 1945. We were married until 1993. He had a heart attack and passed away. I’ve been by myself except for the grandkids ever since. One granddaughter, Lara, lives with me now and works at City Market. My grandson, Eddie, lives on the little bit of land I have left on the west side of our property. My dad gave us 240 acres of land if we would clear it up and act like we were homesteading. That was when we first came back here from Arboles. I thought we did what dad wanted us to do. We bulldozed down a lot of oak brush. I think we burned a lot of it. I guess we shouldn’t have because now I think we would have got a good price to sell it for wood. We never had to buy coal, because we burned oak roots. I remember when our two little girls would go for walks I would say, “Take the wagon and bring back roots for the fire.” We got a chance to buy the old forest service office building. We moved the building out to our land and that’s the house you can see right there by Highway 160 and County Road 189. Then a man named Jim Fillmore sold us an old homestead cabin. My dad and husband took it apart and moved it onto our ranch. That turned out to be our house where we raised our daughters.

Then in the winter he got his call to go to Denver for his physical exam for the army. He never did have to go because the war ended that summer. So we decided to get married in the end of August in 1945. We were married until 1993. He had a heart attack and passed away. I’ve been by myself except for the grandkids ever since. One granddaughter, Lara, lives with me now and works at City Market. My grandson, Eddie, lives on the little bit of land I have left on the west side of our property. My dad gave us 240 acres of land if we would clear it up and act like we were homesteading. That was when we first came back here from Arboles. I thought we did what dad wanted us to do. We bulldozed down a lot of oak brush. I think we burned a lot of it. I guess we shouldn’t have because now I think we would have got a good price to sell it for wood. We never had to buy coal, because we burned oak roots. I remember when our two little girls would go for walks I would say, “Take the wagon and bring back roots for the fire.” We got a chance to buy the old forest service office building. We moved the building out to our land and that’s the house you can see right there by Highway 160 and County Road 189. Then a man named Jim Fillmore sold us an old homestead cabin. My dad and husband took it apart and moved it onto our ranch. That turned out to be our house where we raised our daughters.

B.L.: Tell me about when you started teaching at the Bayles School house.

EN: When I was in school a woman named Evangeline Moorhead Catchpole had been my teacher. When I started teaching I had attended only one year of college and I hadn’t had any methods courses and I didn’t know what I was supposed to do, but I remembered how Mrs. Catchpole taught, and so I taught like that. I don’t know if that was what I was supposed to do or not but people said I was a good teacher.

I had seven students from first grade through eighth grade. Sometimes the older kids could help out and listen to the younger ones read. In the winter when we’d build a fire, we’d all put our feet up with our books in our laps and read them. They recognized later that all children don’t progress at the same rate. If you have twenty children in the first grade, you’ve got twenty levels because each child is different. I don’t think the children benefited when the schools consolidated. All these children who had received individual attention in the little country schools were dumped into the same class and expected to all go together. I don’t think the children’s individual needs were addressed as well.

We didn’t have all the sports activities the kids had in the bigger schools, but we had baseball and played with our own rules. I got out there and played with them. I know Mrs. Adams who lived in the house by the school thought we were having too much fun, and that the kids should be inside studying more.

It was fascinating to hear Mrs. Nossaman’s story. I envied the sharp details of her memory as she shared a piece of Archuleta County’s educational history. Her kindness and sincere care for her students and their education has certainly impacted many people in our community.