In 1933, Frank graduated Phi Beta Kappa in three years from Johns Hopkins University, where he was awarded a scholarship as a top member of his class. He then spent a year and a half in the Cavendish Laboratories in England—the laboratory of Sir Ernest Rutherford—working on natural radioactivity with C .E. Ellis and other greats in physics.

He was invited to work on the development of nuclear particle counters at the physics laboratory in Florence, Italy, and again had contact with many of the greats in the field, including Ochialini and Bernadini. All the while, he continued to play the flute (he was a member of the Bach Club in Baltimore); pursue his interests in art (he got to know personally almost all the paintings in the Uffizi Gallery while in Florence); and embark on new adventures (while in England, he earned a pilot’s license flying a Gypsy Moth—a specimen of which is now in the London Science Museum).

On returning to the United States., Frank spent four years at the California Institute of Technology earning a Ph.D. and working on artificially induced radiation. He subsequently became a teaching assistant in introductory physics and optics at Stanford University for two years. He also worked with Felix Bloch on neutron physics at this time.

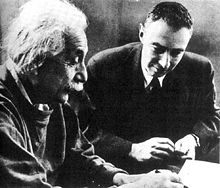

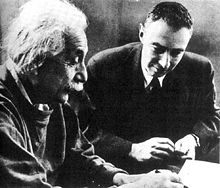

Einstein and Robert Oppenheimer.

Einstein and Robert Oppenheimer.In 1941, he began work on uranium isotope separation at the Radiation Lab in Berkeley, where he was a group leader on the project. He remained a research associate at Berkeley on the Manhattan Project (directed by his brother, J. Robert Oppenheimer) for four years, during which time he spent several months at Westinghouse supervising the manufacture of isotope separation devices (calutrons), and eight to ten months at Oak Ridge National Laboratory where he was valued for his boundless energy and ingenuity.

Frank arrived at Los Alamos in 1945—rather late in the story, but in time to serve as the tireless executive officer to Kenneth Bainbridge, who was in charge of planning and conducting the first atomic test at Trinity of the first plutonium implosion bomb.

Frank’s experiences at Los Alamos convinced him of the seriousness of the gap between scientist and layperson—and the importance of making an understanding and appreciation of science accessible to the public at large.

After the war, Frank worked on the development of linear proton accelerators with Wolfgang Panofsky and Nobel Prize winner Luis Alvarez. He did the first experimental work on the newly completed 194-inch cyclotron in 1947. During this period, he was asked several times to direct the research on nuclear energy for the propulsion of aircraft.

In 1957, he was drawn back into education as a science teacher at the local Pagosa Springs High School, which had fewer than 300 students and only one science teacher for all the grades. A tireless and innovative teacher, he took students to the dump and used abandoned auto parts to teach principles of mechanics, heat, and electricity.

In 1965, Oppenheimer began the melding of his interests in peace and humanity, scientific research, teaching, art and history, philosophy, and museums that a few years later would blossom into the Exploratorium.

Oppenheimer Ranch on the Blanco Road from this website.

The Exploratorium opened officially in 1969. It soon became established as the “best science museum in the world” according to Scientific American and many others; some early visitors from Beijing called it “the people’s science museum.” Representatives from museums throughout the world have visited the Exploratorium for the specific purpose of planning a new science museum or improving an old one.

It took courage, resilience, and dedication for Frank to pursue his dream. He accomplished—over and over again—that which many said could not be done. The Exploratorium is a remarkable and tangible culmination of one man’s life, experience, and ideas. Everyone who has been there cannot help but feel that their lives have somehow changed; that they have gained a new awareness of themselves.

The Exploratorium

In 1960, Frank delivered a speech to the graduating class of Pagosa Springs High School, a small Colorado school where Frank had been the sole science instructor from 1957 to 1959. Portions of this speech, which dealt with how to live a rich and fruitful life, seem appropriate.

I am grateful for the life I have lived. It has certainly not been as full as the lives of some people, and yet it has probably been richer in experience and in a sense of accomplishment than the lives of many.

I think that part of the sense of having lived a full and a rich life comes from an ability to continually take things seriously, but not too personally. This feeling stems from a willingness – even a determination – to become deeply involved in what you are doing, but not obsessed by it.

I want to put a little more meaning into the phrase “taking things seriously.” Perhaps I can best explain what I mean by talking about myself. I would say, for example, that I took my teaching in this school seriously. First of all, I thought it was an important job. I felt that if you learned some science, you would be able to lead better lives. And I felt that by trying to do a good job of teaching, I might have some effect not only on you individually but also on the school and the community. The teaching involved a lot of work and planning and I had to learn new things, not only about the subject matter, such as the names of the various geologic epochs, but also about how to present ideas that I was, at first, not able to get across. I stopped thinking of myself as a rancher or a nuclear physicist and thought of myself primarily as a high school teacher and wanted to be a good teacher. I wanted you to understand the things I enjoyed understanding, such as why a star got hot and stayed hot. I wanted you to get satisfaction from being able to do some of the things I found pleasure in doing, whether blowing glass or solving a problem. I felt an enthusiasm for the whole process of teaching. Now let me give you another example, in retrospect a quite trivial one. At about the time I graduated from college, I took coffee seriously. I read about coffee and found out where and how it was grown and roasted. I wandered about New York City looking for coffee import houses, bought my own grinder, and learned to tell the difference in taste between Mocha and Java and Guatemalan and Brazilian and Costa Rican coffees. I drank my own mixtures and occasionally served them to my friends, each type of coffee for the proper time of day. Undoubtedly my friends thought I was nuts, but I thought of myself as a connoisseur, an expert.

Now, twenty-five years later, I can chuckle at my former self. But obviously at the time it was not a trivial interest, or I would not now recall it so vividly. I do not want to relive my life for you, but I would like to mention, for the purpose of example, a few more of the things that have absorbed me. During the War, it seemed enormously important to me that America develop an atomic bomb as quickly as possible and before anybody else did. Now the making of atomic bombs seems repugnant and evil to me.

Before the War, I worked hard and long to help support the Spanish Loyalists against the fascist invasion of France. After the War, I gave speech after speech on the need for nuclear disarmament. During my years here in the Basin, I put my heart into my ranch, trying to make it a better one. I derived pleasure from the flourishing crops and animals, and I learned the sick feeling that comes when one fails in helping a heifer to deliver a live calf or sees four or five cows dying on the range from having eaten larkspur. Before coming here, I was in Minnesota for a couple of years.

I remember how exciting it was when, with our high-altitude–balloon experiments, we discovered that not only hydrogen, but the atoms of all the elements were in the cosmic rays coming from outer space. In thinking about my life, I arrived at some ideas about what was necessary for a fruitful life.

First, you become involved in projects that you can put your heart into. They seem important. What happens, the outcome of your efforts, must make a difference to you. Second, the outcome must have, directly or indirectly, a wanted effect not only on you but on something outside you, on other people or on science or on a ranch or on a business. Third, your project must involve some effort in doing, and especially in learning and experimenting. Fourth, you have to really commit yourself by being willing to stand for something and represent the kind of person to yourself and to others that is not inconsistent with what you are involved in.

In this sense, taking something seriously often means that one is conscious of acting a role.Now this subject of acting a role is a tricky one. There are many people who are thoroughly obnoxious or pathetic because they are continually acting the role of someone they would like to resemble but cannot. The standard cartoon about insane people shows them pretending to be Napoleon. I am not going to try to answer the question of when and to what degree role-playing is proper and appropriate. But I know that to get much out of what you are doing, you have to act the part and be consistent with its restraints and customs.

But I cannot draw for you the fine line between devotion and obsession or between sanity and insanity. It seems that one’s ability to draw this line in any actual situation is connected with the fact that one can take what one is doing seriously without at the same time taking oneself too seriously.It is not easy to explain why people take things seriously. If one thinks deeply and objectively about anything, even life itself, it can appear trivial. One can argue that our actions make a negligible difference to a universe that is billions of years old and a billion light years in diameter. But such thinking is somehow irrelevant to the way humans act.

I am aware of the immensity of the cosmos and yet I can take things seriously. So can you.I do not want to imply that I have no sense of values, and that everything is of equal importance to me. Some kinds of pursuits and exploits that I could have at one time put my heart into, now seem unimportant to me, but other, perhaps somewhat more channeled interests, have appeared in their place. I do not know what will capture my devotion in the future, but from past experience I have some confidence that it will be caught.For you, I hope that there is another domain that will attract you. Throughout one’s life, one sees the perpetuation of innumerable injustices in human acts, both at home and abroad. Usually, one feels powerless to do anything about them, but I recommend to you that when an opportunity to intervene for justice arises, either for you alone or in concert with others, you take these opportunities seriously and consider them important.

I have gone a little astray from my main purpose tonight, which was merely to remind you that you have a long life ahead of you and to say that I hope it will he a good one. I have talked about just one small aspect of how you live your life, but I think it is an aspect over which you have some measure of control and also one that you might not have been aware of. I recommend that you be willing to become deeply involved in lots and lots of things and that you let yourself, perhaps even force yourself, to do the things that you think are important and that you can take seriously. I make this recommendation to you because I believe that if you do, then even in the face of considerable adversity you will feel, as I do now, grateful for having lived.

Einstein and Robert Oppenheimer.

Einstein and Robert Oppenheimer.