The digital universe is not perfect! Sometimes our photos have floated away into the void and do not come back. We were contacted by an academic who wanted to use this story and the photos. They were lost. Recently, after going through a ton of memory, I found a disk where it shouldn’t be and, surprise, there they were! So Nathan, here is the story with the original photos.

Norm

Saving the Kit Carson Tree

Here at The Journal we try to publish an interesting look at the history of the area. Sometimes we research the history and sometimes, while chasing down one story or another, we become the history. This was the case in 2006 when a tip followed up moved us into the story and a historic effort in current times. This is the story of the discovery of an aspen tree with the name Kit Carson carved into its bark and a heroic effort to save this tree from the ravages of time.

Note: At the time my son, Ian Vance, was working for this website and took part in the tree salvage work and did photos for the website.

Kit Carson Tree Carving Discovered

I had an interesting conversation with Ron Bambrick at the now closed Chromo Store. Initially I’d approached him inquiring about the Chromo area and the Price Lakes Forest Access Road, as Ron and his extended family have lived there for well over a half century. I asked for an interesting bit of the past. Ron disappeared into his house and returned with the photograph shown below. The inscription reads “KIT CARSON 1859.” I immediately wondered if this could be true.

The tree was found by Dave Sanchez while hunting for lost cattle by horseback. He was high in the mountains in the general area east of Chromo, and the carving was not along a trail.

Ron revealed that some people have doubted the authenticity of the carving. I did a bit of research and came to believe it is real. Some said that Carson was known to be illiterate, but that does not mean he couldn’t carve and print his own name. Others have claimed that aspen trees don’t live this long. I found an academic biology website that listed the “age window” of aspen as 40 to 150 years. This particular carving is 147 years old, meaning Carson would have etched it on a young tree; Dave reported the tree is near dead. So, time-wise, it isn’t much of a stretch.

A great deal of work and organization was done in short order as the discovery was of importance to many citizens. Area leaders along with outfitters and the Forest Service District Ranger formed a group to go into the wilderness and bring the tree section out. Dave Sanchez is shown here celebrating the effort.

After some research on the internet, I found a similar tree carving from 1844, discovered in Northern California. This carving was done on the trail that later became Carson Pass on California Highway 88. When the tree was cut down, the section with the carving was saved, and it is now in a museum under government protection. The carving is similar in that it is all capital letters and the letters are carved in the same proportions. Another known carving in the San Lewis Valley is the same. There is a forth known Carson carving, but it is different, having lower case letters and a script like font.

There was a great sense of adventure and excitement among the team members. From the Leche Creek Trail Head they rode horseback into the high country. The last stretch was hiked due to rough terrain.

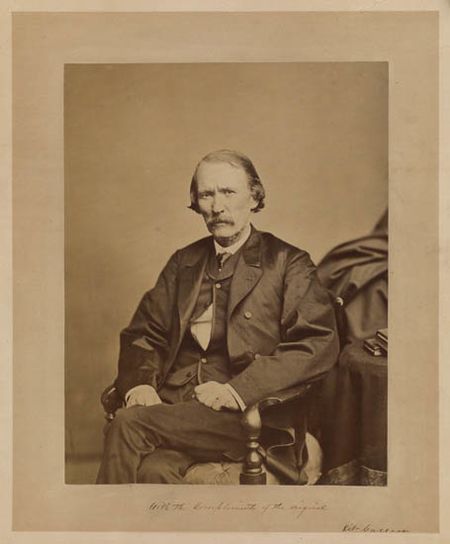

Carson lived at times in the Southern San Juan around 1859. He was the Indian Agent for this area, headquartered in Taos, New Mexico, and was known to travel to the Pagosa region for hunting and fur trapping. There is a historical reference of an injury incurred from a horse accident; “In the fall of 1860, Kit went hunting with some friends in the San Juan Mountains of southern Colorado. On a steep trail his horse took a spill and Kit suffered serious internal injuries. He recovered but was left with recurring pain and physical damage that would eventually cost him his life.”

It is interesting to consider the area at this time. The San Juan Mountains had long been a barrier holding back settlers and exploration. Harsh winters and rugged terrain were quite a bit more than the Spanish or early Anglos wanted to deal with. Settlers learned to navigate and travel east-west by detouring many miles south of the San Juan Mountains on what became the Santa Fe and Old Spanish Trails. Many people traveled these routes, moving west to California. Although the California Gold Rush was over by this point and a good deal of the west had been settled, the San Juan remained an unknown wilderness. Indians roamed as they had for centuries and a few fur trappers worked the area.

Kit Carson at about the time he trapped and carved in the San Juan Mountains.

1859 turned out to be an interesting and important year. During the same summer that Kit was hunting and carving along the western divide, a small band of men crossed into the area just a few miles away. A Captain J. N. McComb led a government expedition through the area, and his expedition produced the first decent map of the region. Following roughly the same route as Dominguez and Escalante from Santa Fe to near the present Colorado state line, the group went farther north before turning west, and their twelfth camp was at what the Indians referred to as “Pa-go-sah.” J. S. Newberry, a geologist accompanying the expedition, commented that the spring was “well known, even famous, among the Indian tribes.” He continued: “there is scarcely a more beautiful place on the face of the earth.” Leaving the spring, McComb led the expedition west along the present route of US 160 and camped two days later on the banks of the Piedra River. Here Newberry described and sketched Chimney Rock.

During 1859 and 1860, Charles Baker and a few miners made their way up the Conejos River directly east and across the divide from Carson’s location and ultimately discovered gold at what would become Summitville. This gold discovery would finally bring population to Pagosa Country and open the area to settlement.

So: men were entering the San Juan at this time, but it is entirely possible they never knew of each other. Taking this circumstantial evidence into consideration, I believe the carving is authentic.

The top of the tree was removed with a one man saw. It was cut above the carving to lessen chances of damage.

It was the kind of morning that many long time locals think of as “a Milt Lewis-ish kind of day.” Milt was an artist who lived and operated an art gallery on Main Street for many years. He had a style of painting high country morning mountain scenes with clouds of mist hanging in the trees and hazing through meadows. Many of his paintings and posters still hang in the area. That was the scene as this group arrived at the Leche Creek Trailhead. There was an electric feeling in the air as all were excited and eager, if not a bit apprehensive, about the adventure ahead. The apprehensiveness stemmed from the hanging question of the potential success of their mission. Felling a large tree without damaging a specific section is not guaranteed!

This saga began when Dave Sanchez of Espanola spotted the tree while rounding-up stray cattle. Dave holds the grazing lease for the area and knows it well.

There was extended conversation about how to best get the carving section without damage. This view shows the sun damaged side of the tree. Fortunately Carson did his carving on the shady side. The top of the tree was cut away first to lessen chance of damage.

I was talking to Ron Bamrick of the Chromo Store about Chromo area history and he showed me a photograph of this aspen tree with the carving. In the process of obtaining Dave Sanchez’s permission to publish the photo, I talked to Ross Aragon who remembered Dave and had his phone number. Dave gave permission and also told me he was worried because the tree was very old and in decay and that the carving would likely be lost if it fell. I did what I’ve done for years when I’ve needed to know something or get something done, I called Fred Harman!

he lower cut was made with a two man saw. Here Kevin Khung, Pagosa District Ranger on the left, helped. Most of the team wanted a few cuts.

Not only was Fred interested – he knew about the tree. In the early 1940s a man named Bill Flaugh, who had grown up with Fred’s father, found the tree and told the Harmans. When Fred was made aware of the tree’s poor condition he immediately saw the need to save it. Ross Aragon and Jim White, retired Forest Service Ranger, were contacted and a small group formed. Soon the Mayor saw the need and formed an official committee, under the auspices of the Town of Pagosa Springs, with the intention of saving the tree. Committee members are Fred Harman, Betty Shahan, Jim White, David Sanchez and, your writer, Norm Vance.

The retrieval of the tree was complicated by its location in the South San Juan Wilderness. It would have to be cut with a handsaw and hauled out by horseback. A specific quartet of people with talent in the art of mountaineering, tree felling and horsepacking were brought in to help David do the actual job. They were George Love, Clay Campbell and Jim and Lucille Morehouse. Morehouse supplied a Clydesdale Cross horse that was visibly larger in every direction than any other horse there to carry the tree.

Peggy Bergon is an arborglyphs (tree carvings) expert, so she was a natural for the group. Betty Shahan brought her friend Dolly Dillinger. Others in the group included Jim White, Jim N. White, Leigh Gozigian, Mary Helen Cammack, Bob Pargen, Barbara Sanchez and Ian Vance. Ian stood in for me by photographing the event. Fred Harman, Carol Anne White and I waited at the trailhead. Fred manned the radio system for communications.

The weather turned sour with rain pelting down. The tree section was carried under a sling and protected by a tarp.

One of the outfitters brought a huge horse. The section was loaded on one side and a counter balance on the other. The horse managed the load with no problems.

The tree was encased in this glass display and spent many years in the Fred Harman Museum. Stay tuned here for an exciting update on a new location for the now famous tree.

For a history of Kit Carson see;

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kit_Carson

.