Treasure and treasure hunting have become wildly popular with the public recently judging by the plethora of television shows on the subject. Oak Island, treasures of the Civil War and both World Wars along with historic individuals like Jessie James and Butch Cassidy just to name a few. Well, Pagosa has its own history of lost and found treasures. The story below outlines one interesting gold find.

Norm

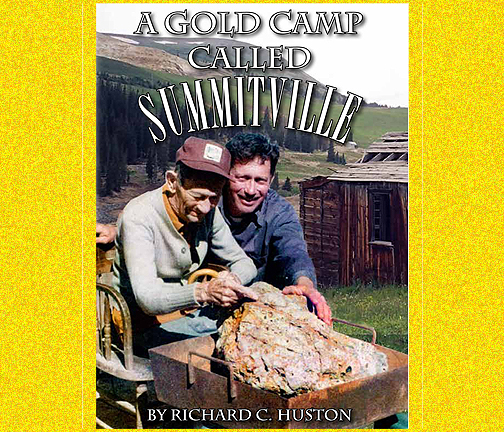

The largest gold nugget found in America was at Summitville, Co. It was gold that brought white settlers to the Pagosa area.

In the spring of 1870, five Union Army veterans followed the South Fork of the Rio Grande River up to a stream that ran along the base of 13,000 foot South Mountain located in the “Alps of America.” There, at a place they named Wightman Fork, the discovery of some promising gold nuggets led to more prospecting and the eventural formation of the Summit (Summitville) Mining District in the then Colorado Territory of the United States. From a brilliant beginning to an ignoble ending, Summitville thrived, survived, and ultimately died, still boasting a history of the richest ore deposits in Colorado’s mineral-rich San Juan Mountains. In A Gold Camp Called Summitville, the area’s geology, its mining bonanzas, and personal recollections and revelations are woven together to paint an accurate picture of the company town of Summitville and the demanding life above 11,000 feet elevation.

The Summitville gold boulder is Colorado’s most remarkable chance discovery of gold in recent times. In 1975, geolgists surveyed Summitville’s low grade gold resource on south Mountain. The only free gold specimens found contained particles barely visible and no one expected to find much more. But on the afternoon of Oct. 3rd, an equipment operator noticed a large rock lying in full view just off the shoulder of a public road below the early mine ruins. The rock was gleaming back at him in the sunlight. He was shocked to find it laced with native gold. Returning excitedly to camp, he asked the project geologist if he wanted to see some gold. The geologist casually agreed, but when the operator said it would take both of them to put it in the pickup, he suspected a joke.

The specimen turned out to be, literally a “gold boulder”. The 141 pound boulder of breccia consisted of silicified vuggy quartz latite fragments cemented together with a matrix of fine grained crystalline quartz and barite, and crystallized gold. The boulder had apparently moved down hill by natural processes from the Little Annie Vein to the point where it was discovered. The geologists believed the boulder had been fully exposed by the road-side for at least thirty years. Specific gravity tests determined that the boulder contained about 350 troy ounces of gold.

Ownership of the Summitville gold boulder became a complicated issue. When the operator first reported the boulder, the company geologist verbally agreed to his request to keep half of it. “Traditionally, prospectors providing mineral location information received a 10% finders fee, if the find was worthy of claiming or development. But the gold boulder was alluvial float found on patented ground. The operator was a paid private contractor and finally accepted an offer of $21,000.

ASARCO kept the find secret for a year to avert a “gold rush”. The company finally announced the find in Nov. 1976, just as Summitville was snowed in for the long winter. With the agreement of the landowner, the Reynolds Mining Co. donated the Summitville gold boulder to the Denver Museum of Natural History, where it is currently displayed. Because of higher gold prices and added worth as a rare and spectacular specimen, the gold boulder is now valued at over $500,000.

Rockhounds and treasure hunters armed with picks, shovels, gold pans, and metal detectors rushed to Summitville the following spring. ASARCO closed several roads when gold seeker interfered with exploration activities.

If prospectors did find more gold, they never reported it. Nevertheless, the Summitville gold boulder will always be a reminder of the bonanza of the 19th century and that the old timers didn’t find it all.

Stephen M. Voynick