Answering questions or helping with information is a daily part of the job here at The Journal. Most are easy to answer as, “Where are the elk going to be next October?” Others are more involving and interesting. Michael Huffman asked recently about the Cotton Hole Ice Barn and about a place where he and his family stayed in 1948. Michael is writing his memoirs including a description of a family vacation to Colorado in that year. He sent a draft of the chapter including Pagosa Springs. I asked permission to post the excerpt below.

Just the act of driving through Southwest Colorado in 1948 was grand adventure. I think you will find the memories of a seven year old boy as charming as I did. – Norm Vance

This was the first real vacation we took, probably in 1948 or 1949. Although we didn’t really have the money to take a vacation, Dad went to the bank and borrowed $75 for us to be able to spend two weeks in Colorado. That first year (we returned to Colorado three or four more times in the subsequent years), Mom and Dad owned a 1935 Ford four-door sedan. Gasoline prices hovered around the twenty-cent-a-gallon mark. To prepare for the trip, Dad built a platform between the front and back seats, level with the seat cushion, to serve as a bed for us kids. Camping cots were strapped to the rear bumper. Hanging out the passenger window was a rudimentary “air conditioner” of the day—a mobile swamp cooler, which caught air while we drove, passed it over wetted excelsior pads (fine, spiral wood slivers—sometimes called “wood wool”), and directed the cooled air into the interior of the car. In the very low humidity of west Texas and New Mexico, it worked remarkably well. Hanging in front of the radiator was a canvas bag filled with drinking water; the water would gradually seep through the canvas to be evaporated by the wind and thus cool off the contents.

So, off we went, northwest through Abilene, Sweetwater, and Lubbock. The trip out probably took three days. Although there no doubt were tourist courts along the way, we didn’t avail ourselves of them—they cost too much. Instead, we camped out, simply pulling off the road at a likely spot and pitching our camp. We had a Coleman cook stove and a Coleman lantern; the fuel was not propane as today, but “white gasoline,” which was gasoline without the tetraethyl lead additive for automobile fuel. To light the stove or lantern, I sometimes got to pump up the tank with a built-in piston pump to create enough pressure to force the gasoline into the burner; once it was going, the heat produced enough pressure to continue the flow.

Michael is interested in knowing where the family stayed while in the Pagosa area. It was a few cabins on a ranch near the confluence of the East Fork, the West Fork and Wolf Creek. The owner or person in charge was Vic Johnson.

Mom made sandwiches for lunch and cooked good meals for supper. She brought along her pressure cooker, knowing that at the higher mountain elevations, water would boil at much lower temperatures, making it difficult to cook potatoes, meat, and vegetables. In the evenings, we also generally had a campfire, which by itself was a fascination for us kids.

I think Patty and I slept in the back seat bed of the car, with Dan in the front, while Mom and Dad slept on cots outside. If memory serves, we did not take a tent on that trip.

On one of those stops, a funny thing happened. As usual, Dad had chosen a spot with a windmill and a stock tank near the road, so we could get water in the morning before we left. Just about the time we all got settled down for the night, the wind shifted directions and a horrible smell swept over the campsite. We tried to ignore it for awhile, but it kept getting worse, coming from the direction of the windmill. Finally, Dad investigated and found that a cow had died some days before right next to the stock tank. Late that night, we had to strike camp, load up the car, and find another campsite.

From Lubbock, it was north to Amarillo, then northwest through Dalhart to Raton, New Mexico and Trinidad, Colorado. Then west through Alamosa—all flat land the whole trip up to then. Finally, at South Fork, Colorado, we began the upward climb of the magnificent Rocky Mountains. As we climbed, I was taken by the cooling air, the dense pine forests (totally different than the isolated islands of live oak in Texas), and the grandeur of the cliffs and ridges. We crossed the Continental Divide at Wolf Creek Pass, elevation 10, 800 ft., then began the downhill ride into Pagosa Springs.

Before leaving Texas, Mom and Dad had made arrangements for us to rent a cabin east of Pagosa Springs at the farm of a Swedish man named Vic Johnson. I don’t remember much about the cabin itself, but there were other interesting things on the farm. One was the irrigation ditches Mr. Johnson had dug from the river to provide water for his fields. I had never seen anything like it in Texas—canals about three feet wide cut through grassy fields and flowing with cold, clear mountain snow melt water. The water was pure—we kids loved to get a dipper full and drink it, if for no other reason than the novelty. We also enjoyed Mr. Johnson’s animals, which included a few goats we could pet. In the back of his property was a cold, fast-running mountain river with a rocky bed. Dad spent some of the time we were there fly fishing for rainbow and brown trout, which we feasted on in the evenings. Patty, Dan, and I would sometimes go with him to the creek. It was a totally new world to us. With his help, Dad let me wade in the creek; the water was probably not a foot deep, but to keep from being swept downstream by the swift current, each step was a challenge. Dad taught me to choose a likely rock at the location of my next step and to firmly plant my galoshed foot on the upstream side, against the rock.

As it turned out, Mr. Johnson had something else that made an impression on Dad. The two of them had gotten on very well, and as they “chewed the fat” before supper one night, Mr. Johnson invited Dad to have a little taste of his homemade blackberry wine. Now, Dad was not a drinking man; in fact, for the whole time I was growing up, we never had alcohol of any kind in the house. It wasn’t that Mom and Dad had objections to it on religious grounds or anything like that; they had just seen some of its effects— most notably on Dad’s brother Hap—and had made the decision early for very practical reasons (which would later have a funny consequence while I was in high school).

Anyway, Dad did have a little taste of the wine—perhaps two or three glasses full! It apparently tasted like fruit juice and it kind of snuck up on him. Just about the time he finished the last glass, Mrs. Johnson called us all in to supper. Although I don’t recall, it was widely reported in later years that Dad was very happy and talkative at supper. At one point, he apparently picked up a jar of jelly and, reading the label, expressed his surprise that it had been made in “Oklahoma City.” From her later reactions to such nonsense, I imagine Mom sat there with her lips tightened into a fine line. At least not all the family legends are about me.

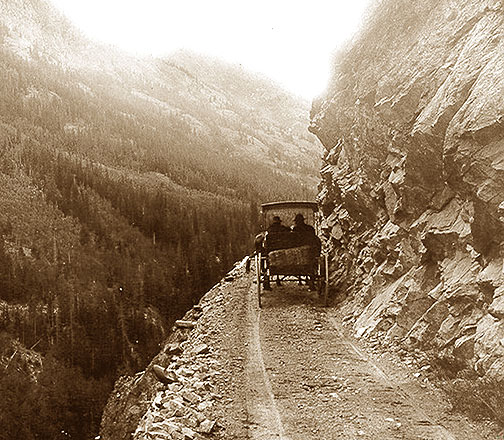

One of the days we were there, Dad took me with him into the small village of Pagosa Springs to buy some ice. I don’t remember anything about the town, but I do remember the building where we got the ice; it was a large barn just off the main highway, sitting on the banks of the river. As we walked in, I absently assumed there was an ice-making plant somewhere in the barn. However, I did notice that the barn was full of sawdust piled high against the wall. Dad talked to the man in charge, who led us to one of the sawdust piles. He began digging and, to my utter surprise, uncovered large blocks of ice buried in the sawdust. Dad told me that the ice had come from the river; in the winter when it was frozen more than a foot deep, the employees would take large saws out onto the ice and cut out the blocks, pulling them by sled into the barn to be covered with sawdust. With that insulation, the ice would last all summer long. I had never heard of anything like that! During our stay, we traveled around southwestern Colorado taking in the marvelous sights. I remember Dad being incensed at having to pay the outrageous price of thirty-three cents a gallon for gasoline.

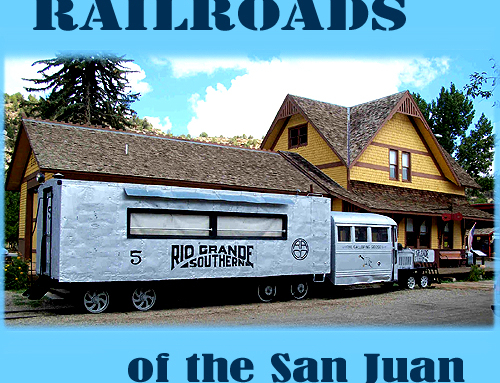

Million Dollar Highway at an early time.

By far, the trip I remember best was from Silverton to Ouray, about 24 miles on a road euphemistically known as the “Million Dollar Highway”; legend has it that the name came about because the road cost a million dollars a mile to build. It rises from about 9300 feet elevation at Silverton to more than 11,000 feet at Red Mountain Pass, then falls in the next couple of miles to about 7800 feet at the little town of Ouray, nestled in a mountain valley. In that day, the road (it would be a great stretch to refer to it as a highway) was simply a steep, rocky notch carved out of mountain. It was dirt the entire length and for miles at a stretch would be wide enough for only one car to pass, with a sheer rock wall on one side and a sheer cliff on the other—there were no guardrails. I remember Dad worrying about the mechanical brakes on the ’35 Ford, which were not too good at best and certainly not suited to mountain driving. At one point, we met a truck coming the other way and had to back up a couple of miles to find a place wide enough for the two vehicles to pass.

At some points, the sights off the cliff side took our breath away—thousand-foot drops with nothing but air from the top to the bottom. At a couple of places where the road was wide enough, Dad would pull off. He would go out to the edge of the cliff and sit down; in that stable position, he would invite each of us to come out and look at the view. When it was my turn, he made me crawl on my belly when I got within about ten feet the edge. As I reached him, he grabbed the waistband of my pants at the back with a very firm grip. I remember having a really funny feeling in the pit of my stomach as I hung my chin over the edge of the precipice. What a great adventure! In about 1987, I visited Colorado and drove the Million Dollar Highway once more. Although it is now a modern, paved two-lane road, there were still treacherous stretches with no guardrails. It was great to have something I remembered as very adventurous when I was a child continue to impress me as an adult. On the return trip to Texas, we took a different route, south out of Pagosa Springs to Sante Fe, then through Clovis, back to Lubbock and back home. North of Sante Fe, we stopped at the famous tourist destination known as Camel Rock. Several photos show us perched next to the famous head. As I wrote this in 2009, I looked up photos of Camel Rock on the Internet; it is still there, looking exactly as it was then, except that the large rock we were sitting on for the pictures has, in the last fifty-two years, slid down the hill about twenty feet.

This photo was in Michael’s family photos. He doesn’t know why as it isn’t in his memory as the place they stayed. I asked Fred Harman. This is his reply, “I’m sure that was the Witt Newton ranch house. My dad worked there when he was a Kid. He did a small oil painting looking east from the ranch house which is in my museum.

The road has changed a lot. The road went close to the house at the At Last Ranch and continued on just a bit to the Witt Newton ranch. I would guess approximately ½ mile. As you head toward the pass you can only see just a flat piece of ground and that was part of Witt’s property. The highway now goes thru where the house was.”

I would bet this was a very impressive ranch in 1948 overlooking the San Juan River in a magnificent setting and the photo may have been taken just to remember it. Ed.

Scenes around Pagosa Springs during the same time.

These two do Pagosa High School’s first ever protest. The sign reads, “Mullins unfair to students.” Mullins was the town barber and sat on the school board. He had fired one of the student’s favorite teachers. The protest didn’t work. Interestingly, Williams Lake is held in by Mullins Dam.

High school plays have always been part of the experience.

Many lives have come and gone while keeping Pagosa Springs alive in this mountain environment. There were great lives lived with great fun and adventure.