The Colorado Agritourism Association came about as an outcome of the Agritourism Strategic Planning process initiated by the Heritage/Agritourism Program within the Colorado Tourism Office. After visiting numerous communities, inter- viewing farmers, ranchers and producers, it was made clear to us that an association was needed to represent the voice of the agritourism businesses.

You told us that you needed limited liability legislation, better insurance products, fair zoning and use assessments on lands, improved sign regulations, and finally, help with marketing. The Colorado Tourism Office has many ways for you to connect to their PR and marketing opportunities – many are free. Take time to get your agritourism business and events listed on COLORADO.COM by visiting INDUSTRY.COLORADO.COM!

This is where we come in. The Colorado Agritourism Association is a nonprofit, here to work on your behalf to navigate the legislative process, find solutions to insuring and zoning roadblocks, develop a sign program, and help you develop your business model.

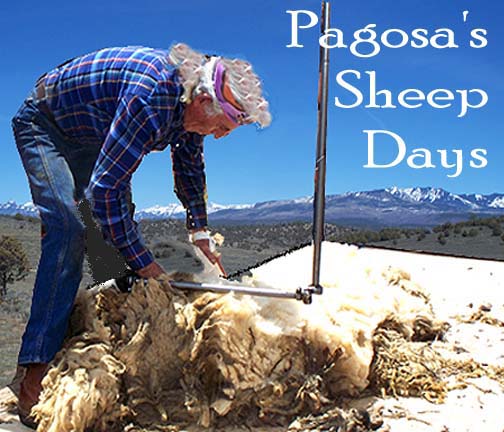

The art of shearing livestock has a long history in Pagosa Country. As you will see in the accompanying article below, this was a sheep ranching area from the earliest days of settlement. Sheep are still ranched here but several alpaca ranches have bloomed in recent times. The Alpacalypse Ranch , operated by Kathleen Conway, is one of these. Saturday was shearing day at the ranch with workers removing the thick alpaca coat grown over the winter season.

Sharing the Best of the West Convention

The alpacas certainly cannot complain about the ranch’s view. Located a little southeast of Pagosa Springs, it is a lovely location.

A professional shearer is brought in making the process as quick and painless as possible. The alpaca has ropes tied to its hooves and is stretched between solid objects enabling long quick shearing strokes. Others are quick to gather the fur and put it in bags.

Now, isn’t that better? As daily temperatures rise it must feel great to have the thick coat removed.

Kathy takes advantage of the situation and trims the hooves.

Now continue reading a history of the sheep ranching days of Pagosa Country.

The following text Courtesy of Center of Southwest Studies,

Fort Lewis College

The Center of Southwest Studies, Fort Lewis College

TCP=Traditional Cultural Properties

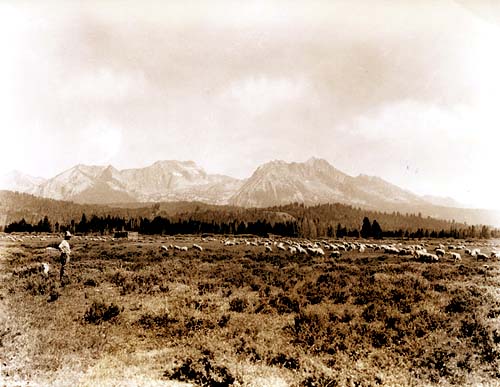

Sheep grazing

Valleys in the headwaters of the San Juan River and its larger tributaries, such as the Piedra River, offered excellent grazing land, with stock numbering in the thousands. When Ernest Ingersoll visited Pagosa Springs in 1882, he observed:

The vicinity of the springs is destined to yield large crops under irrigation, though at present there is little settlement there. Mexicans pasture their sheep as thickly as the fields will hold them; and try to give their flocks a few days in the basin at least once each season, believing that the drinking of the waters is of great benefit to the animals. . . . [The] upper part of the San Juan is unlikely to prove very profitable as agricultural land.

By 1890, according to Archuleta County’s assessment roll, there were 3,509 head of cattle, 17,840 sheep, and about 1,000 horses. By way of comparison, the number of sheep in all of Colorado in 1886 was two million. The economic downturn of the 1890s, due to both drought and depressed silver mining, seriously impacted all industries in Colorado, including sheep raising, and their market plunged. Following a recovery, by 1903 there were estimated to be in the San Juans 86,100 sheep which were owned in New Mexico and about 182,000 which were owned in Colorado, totaling 268,100. A report on the proposed San Juan Forest Reserve in 1903 listed the industries of the area as farming, sheep and cattle raising, lumbering, and mining, in that order of importance. In southwestern Colorado sheep outnumbered cattle by about three to one.

As available land and forage at lower elevations became insufficient year-round for large numbers of livestock, grazing practice had shifted in the 1880s from free roaming in valleys, mesas, and foothills to herding on mountain pastures in summer. Sheep thrived on alpine grasses and could negotiate rocky terrain but were destructive of ground cover and trails in lower areas where cattle could graze, with consequent quarrels between owners of sheep and cattle. By 1900 contention about preferred pastures, as well as ethnic conflict, frequently resulted in injury, murder, and killing of livestock. In western Colorado, hostility was especially virulent north of and along the Gunnison River, worse than in the San Juan area, although it existed there as well.

Generalizations that Anglos were cattlemen while Hispaños were sheep men do not always hold true, nor does information that one county or another was grazed solely or even primarily by cattle or sheep. Incorrect, too, are, the preconceptions that Hispanics did not own their own bands of sheep and that hired sheepherders always were Hispanic. As examples, the Archuleta family grazed large numbers of sheep on Archuleta Mesa, near the confluence of the Navajo and San Juan Rivers. The Stollsteimer family, part Hispanic, also owned large numbers of sheep, which they sold to Sargent at Chama. Some of the San Luis Valley’s major sheepmen also were Hispanic. And some of the herders were Ute or Navajo Indians.

Another outstanding example, Luis Montoya of Del Norte, refutes the ideas that Rio Grande County was used only by cattlemen during the grazing wars and that Hispaños did not own their own sheep. After operating a thriving freighting business between Del Norte and Summitville, he turned to ranching and raising sheep, the occupation his father and his brother also pursued. Some of Luis Montoya’s sheep were herded at Alberto Park, which Montoya named for his friend Albert Pfeiffer. This basin and Alberto Peak on the Continental Divide are at the Wolf Creek Ski Area, with spelling changed to “Alberta.” Another of Montoya’s friends was Ute Chief Ouray, who owned large numbers of sheep. Luis Montoya managed Ouray’s flocks. Montoya was the leading sheepman in southern Colorado with 10,000 sheep in the 1890s. As was customary, each of Luis’s sons was given a farm and a flock of sheep when he married.

Luis Montoya’s great granddaughter, Sarah Martinez, has described the high-country meadows where her family lived in a log cabin in the 1920s. The grass was about three feet tall, high enough that she recalls being able to hide in it when she was about six years old. Her father pastured sheep nearby, but no cattle, although the family had some milk cows.

The story of the José Adolpho White family of the San Luis Valley and the La Garita Stock Driveway have been described by his grandson, Frank White. When José first arrived in the Valley from New Mexico, he worked for early settlers, Espinosas and Trujillos, who had come in 1858 with sheep, goats, horses, and necessities for starting their ranch which was located at Carnero (now called La Garita). They gave White a few sheep and some land at La Garita Canyon, and he was able to buy the Espinosa property in 1894. He prospered as a sheepman. After the U.S. Forest Service came into being, sheep men in this area used the La Garita Stock Driveway. From La Garita Canyon, this driveway followed a trail that once had been used by Indians between the San Luis Valley and the Uncompaghre county and the San Juan Mountains.

When Forest Reserves and National Forests were created before and after 1900, grazing quotas and a permit system were established. Several stock driveways gave access to sheep, cattle, and horse pastures. Livestock, heading to allotments on forest land, were counted in pens at the entrance to driveways, and permit holders were assessed fees by animal units per month (AUMs). Originally, the allotments were for sheep, cattle, or horses. As horses that were used for transportation declined in numbers, horse allotments were eliminated, and some allotments became designated for “cattle and horses,” as some still are. Rangers checked allotments during the grazing season and often found livestock missing or on the wrong allotment. Despite many documented disputes involving cattlemen versus sheepmen, contention also occurred when sheep trespassed on an allotment that was leased to a different sheep permittee. Cattlemen were unhappy because fees per unit for cattle were about five times as high as for sheep. Despite resentment about fees and governmental interference, the advent of federal control helped reduce conflict and violence between people grazing cattle and sheep on public lands. In 1934 the Taylor Grazing Act introduced grazing regulations to other public lands that had not been covered previously by the national forests or reserved for other purposes.

In the San Luis Valley it was common for farming and sheep growing to go hand in hand. In early years of settlement, sheep came in handy for threshing grain, and in the first part of the 1900s farmers in the San Luis Valley who were growing large quantities of green peas and field peas put sheep on the cropland in winter, effectively cleaning up the fields and fertilizing them simultaneously. The sheep were moved to summer pastures on allotments in the Rio Grande National Forest.

Partido system

Many owners of sheep “rented” bands to individuals who hoped to build up their own flocks. With this system, called partido, an individual contracted with a sheep owner to herd a band with the understanding that a certain percentage of the increase would become his. The herder risked going into debt to the owner if the flock decreased while in his care, but by means of the partido, system, many Hispanic herders were able to accumulate their own flocks. A notable example was Luis Rivera, who started by herding for others and eventually acquired his own large flocks. He is well remembered as a rico, a prosperous patron of the Catholic Church at Capulin and a banker in La Jara in the San Luis Valley.

A variation of the partido system was a contract used by Frank Bond of Española, who had mercantile stores and wool warehouses in the Chama River Valley and southwestern Colorado. Ed Sargent, who had warehouses in Antonito and Chama, also practiced this variation. These entrepreneurs used a contract that rented sheep for three to five years in exchange for wool at two pounds per head. This contract also involved risk to the renter, and indebtedness ensued.

Herders

In the early years of settlement in the San Luis Valley, herders were the young sons of Hispanic settlers or captive Indian boys, who tended the livestock on open land in the Valley, without the necessity of going to high pastures. As available land decreased, grazing moved up to mountain pastures. The herders most often were Hispanic boys and men who returned to their homes in the Valley for the remainder of the year. Native Americans also were hired.

An example of a family operation in the 1900s is that of Frank White. While he was a boy, Frank helped herd his family’s sheep in the San Juan Mountains. On the way up and down the La Garita Driveway White often found arrowheads and noticed “designs and markings” left by Indians. He also found tree stumps, which he believed Frémont’s party had cut during the disastrous expedition of 1848-1849. It is rumored that his grandfather long before had found the cache left by the Frémont party, and with the money he established his flock of sheep.

At a young age, herders became self-reliant. They normally camped in tents in the high country. Nights were cold, and rain or snow could make conditions miserable. At night the howling of coyotes and the hooting of owls added fear to the loneliness. Unless a sheep owner provided “store-bought” delicacies like potted meat and crackers, food usually consisted of beans, jerky, and coffee, supplemented by rabbits, squirrels, fish, and sometimes poached game. In the high country, edible wild greens and berries were scarce, but in sub-alpine country wild raspberries, wild currants, chokecherries, and rose hips were tasty additions in late summer. When illness or injuries occurred during the drives or in camp, remedios were at hand. Lore of folk medicines was well known and the materials for them were gathered—arnica, juniper berries, canaigre, thistle, wild onion, rabbitbrush, sagebrush, dandelion, evening primrose, bee plant, willow, yarrow, mint, wild tobacco, wild parsley. Where terrain permitted, some herders enjoyed the comforts of a sheepherder’s wagon with a small stove and a waterproof roof, but work still required a herder to be outdoors, often in inclement weather.

Herders had to keep their bands together and off poisonous weeds such as Loco Weed. Dogs helped by herding sheep, gathering strays, and protecting bands from predators such as bears and mountain lions but most especially coyotes. Burros and horses brought supplies from Creede and similar points in the lower county, but otherwise the herders were on their own, often with no company except the dog. As recently as the mid-1980s, Virginia Simmons, while camping, observed pack animals carrying supplies and blocks of salt on a trail leading from the La Manga Pass area into the south San Juans. Another time, a Mexican sheepherder with his dog tended a band of sheep while a short-wave radio played music from Juarez. In recent years there have been a few Basque, Mexican, and South American herders in the San Juans, as it has become harder to find herders willing to spend summers alone in high pastures.

In earlier years, herders were often men or boys from villages and small farms in the Conejos River area, whose extended families had settled on what was the Conejos Grant at the time. They had large families, and, as lands were parceled out to sons, the owners no longer were self-supporting so they accepted jobs. Loss of land to homesteaders or to new purchasers, and loss of water rights were additional causes of change. Virginia Simmons has personally been told of two incidents, illustrating that land loss was not easily accepted. In one instance, an Hispanic grandfather was shot and killed as a trespasser on land that had once belonged to him in Conejos County. In the other instance, an Hispanic man killed a cattleman who was trying to get land in Rio Grande County.

An oral interview with Jack Sylvester, who grew up at Center, Colorado, offers much detail about the life of a herder. He was born during World War I into a sheep-ranching family and grew up helping with sheep at home and herding sheep around the headwaters of the Rio Grande, in the area of Ute Creek. Following lambing in May and shearing around June 1, a crew of three to five herders would prepare to spend twenty-three days on the trail to the mountain meadows. Sheep were “counted in” at the corrals on June 20, and they were required to be back by September 15. He recalled the monotonous diet of mutton and beans, mutton and potatoes in camp, but he also fondly recalled the dogs, which responded faithfully to orders.

Although some ranchers did their own shearing, crews of Hispanic shearers went from ranch to ranch. While most worked in their own regions, some crews traveled great distances. Around 1900, J. C. Lobato, sheriff of Costilla County, was contracting to send crews to shear large flocks as far off as Nevada and Montana. Besides the expert task of shearing, “wool stompers” were hired to pack the wool into large bags, holding three hundred pounds of wool.

Marketing lambs and wool

In 1882 Ernest Ingersoll provided his observations about the value of sheep in southern Colorado:

[Antonito, which Ingersoll calls by the earlier name “Conejos”] is the headquarters of sheep and cattle men of the San Luis Park [Valley]. In sheep, I learn that although about two hundred and fifty thousand are sold out of the park annually, fully five hundred thousand are left. The large majority of these are of the inferior sort called Mexican sheep, which are worth from one dollar to one dollar and twenty five cents a head. The better minority will sell at one dollar and fifty centers and two dollars a head, and this minority is increasing though a constant effort to improve the breed by introducing highly bred Merino and Cotswold rams. The average yield is two and a half pounds of wool annually, and the product is shipped almost entirely to Philadelphia, for use in making carpets. Cattle is less an industry here, because the sheep are so numerous as to consume most of the pasturage. Something like ten thousand head, however, are able to exist in the park and adjacent foothills, and are sold to great advantage.

Along the San Juan Extension of the D&RG, thousands of head of sheep and cattle were shipped each fall. Along the line, herders brought their bands to corrals, located at sidings where livestock was loaded into stock cars for their journey east. Chama and Osier were important shipping points in the mountains, while towns like Antonito, La Jara, and Del Norte in the San Luis Valley were filled with dust and the bleating and bawling of livestock. Narrow-gauge stock cars for sheep had two levels, into which the sheep were led by a “Judas goat.” In the San Luis Valley, an informant has said that many of the sheep were shipped under contract to Kansas City, where the contractor paid for freight as well as for animals. On the west side of the Divide, stations like Arboles and Chama were important. Later, trucks replaced shipping by rail. Dipping vats for sheep or cattle were used to kill diseases and ticks. These were located near points for shipping, whether by train or by truck. Beside a road in Saguache County, a deep trench, lined with concrete, had been cut in a low rise for use with cattle. Nearby were a boiler and a corral. A shallower trench would have been required for sheep.

In the fall, Jack Sylvester reported, his father sorted the lambs and sold about ninety percent, while keeping the rest to breed. Ewes cleaned up the fields in the winter, and some old ones were sold as mutton to Indians and Mexicans. Sylvester said that a sheep ranch had only two pay days, one being when wool was sold and the other being when lambs were sold.

After a slump in prices during the 1920s and 1930s, World War II revived the market for sheep and wool. The military fed mutton, not lamb, to soldiers, who retained a distaste for this kind of meat after the war. Large quantities of wool went into uniforms. In 1954 sheep and wool industry received a major boost when the National Wool Act provided a subsidy to supplement what growers received for wool and mohair, a goat hair. The development of synthetic fabrics similar to wool became increasingly available, and the subsidy was lost in 1995. Many sheep growers went out of the business subsequently, despite a new tariff on lamb imports, which were coming principally from Australia and New Zealand. Another negative impact on sheep growing in the late 1990s was the outlawing of commercial poisons for coyotes, which proliferated and created a major problem for sheep ranchers.

Allotments and stock driveways

The use of allotments and stock driveways reflects not only the policies of the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management but also changes in transportation and economics. Prior to motorized transportation, each national forest had several stock driveway, crossing well-known passes, such as Bonito, Hunchback, Wolf Creek, Lizard Head, and many others, plus those winding through the forests without crossing the Divide.

On the San Juan National Forest, the Pagosa Ranger District had three stock driveways. These now are integrated with recreational use and are not used for livestock. For several years, stock has been trucked to allotments. In this district there are thirty-two allotments, and in 2002 none were being used by sheep. Cattlemen using allotments include a Jicarilla Apache and two Hispanic-surnamed permittees.