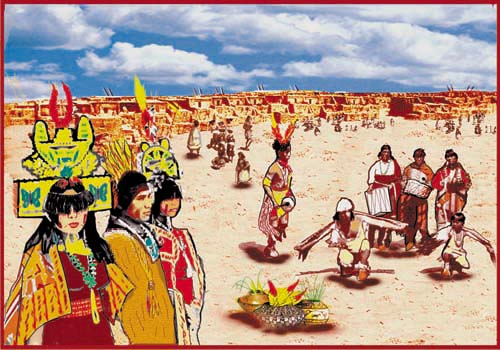

The Ancestral Puebloan people had Koshires or clowns who entertained the tribe.

The following text Courtesy of Center of Southwest Studies,

Fort Lewis College

The Center of Southwest Studies, Fort Lewis College

Artwork by Norm Vance from “The Anasazi Illustrated”

Prehistoric Native American Overview

Native Americans have used and accessed what is now the San Juan National Forest for possibly 10,000 years. Archaic sites have been found on several ranger districts, and this research is best summarized in An Overview of the Archaeological Resources in the San Juan-Rio Grande National Forests by Dr. Philip Duke. A high elevation hunting blind may be found just east of Kennebec Pass where there is a natural corridor for game to flow east to west along what is now part of the Colorado Trail. After the Archaic hunter-gatherers left the area, Basketmaker peoples (? B.C. – A.D. 750) inhabited southwest Colorado planting corn at elevations of 8,000 feet and living in rock shelters, most noticeably the Falls Creek shelter north of Durango. Burials at the site were excavated by both amateur and professional archaeologists and collections from the site are scattered among several repositories. References to Falls Creek include Helen Sloan Daniels: Adventures with the Anasazi of Falls Creek (Occasional Paper #3 by the Center of Southwest Studies, 1976) and Prehistory in Peril: The Worst and Best of Durango Archaeology (1997) by Florence Lister.

Ancestral Puebloan peoples lived in the San Juan region beginning millennia ago, and their habitation sites cover the entire corner of the state though at lower elevations than the Basketmakers. Research on Ancestral Puebloan sites, both in published reports and by contract archaeologists, is voluminous and ongoing thanks to major projects such as the Animas La Plata Project in Ridges Basin, the Fort Lewis College Field Schools which have excavated sites such as Puzzle House and the Pigg House, and the work of the Crow Canyon Archaeological Center in Montezuma County where thousands of archaeological sites have been determined eligible for the National Register. Connections between prehistoric Ancestral Puebloan sites and contemporary Pueblo tribes bear further research, investigation and consultation. Within oral traditions of Pueblo groups, specifically the Hopi and Zuni, their ancestors accessed high elevation sites in the San Juan Mountains and they had ties to habitation sites in what is now the Canyons of the Ancients National Monument.

Because of drought and escalating violence, which may have culminated in cannibalism as a means of social control, by 1300 Ancestral Puebloans had left the Four Corners area and continued their migrations elsewhere. As with all great human migrations, there are both “push” and “pull” factors that stimulate movement. Ancestral Puebloans may have been “pushed” out of the Four Corners area by environmental and social factors, but they may also have been “pulled” to other areas by the new religion of the Katsinas.

Prehistoric: The study area contains archaeological evidence of prehistoric activities from the PaleoIndian periods to the present. Per the National Register definition for a traditional cultural location, a prehistoric site would require confirmation of cultural value from modern informants before a site could be considered a TCP. Many specific site locations probably have lost their meaning to modern descendents, but the descendents may carry traditions associated with a larger area encompassing the specific site location. Certain site types, however, would be more likely to have maintained site-specific importance as a TCP. Sites that are clearly used for resource procurement and appear to have been visited more than once are likely TCP candidates. If reviewed on a larger scale, rather than site by site, certain areas containing a higher density of certain site types could be identified as a TCP. The best sources to further this research would be the site files of the Colorado Historical Society and the San Juan National Forest, and the Colorado Prehistory Context for the Southern Colorado River Basin by Lipe & Varien et al., 1999.

Historic Native American Overview

The time period between 1300 and the coming of the Spanish to New Mexico in 1540 represents one of the most intriguing epochs in southwestern history. Pueblo peoples had moved southeast towards the Rio Grande river valley and Ute peoples moved into Colorado, apparently from the Great Basin area to the West. Uto-Aztecan speakers, the Utes became the mountain people whose territory included all of Colorado, northern New Mexico and Utah. Ancestors of Ute bands now living in southwest Colorado, particularly the Weeminuche, lived on the Uncompahgre Plateau and adjacent San Juan Forest lands. The White Mesa Ute Indians in southeastern Utah, who are enrolled as members of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe, also are a source of information about traditional Ute properties in the western portions of Montezuma and Dolores Counties.

The Athabaskan-speaking Navajos also moved into the Four Corners area from the north but moved south of Ute territory into an area of Arizona and New Mexico and southern Colorado roughly bounded by the four sacred mountains of Mt. Hesperus to the northwest, Mt. Blanca to the northeast, the San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff to the southwest, and Mt. Taylor near Grants, New Mexico to the southeast. They warred and fought with the Utes, and the San Juan River became the northern boundary for the Navajos and the southern boundary for the Utes. Early Spanish accounts describe nomadic peoples as “Apache de Nabajo,” and it is not until later in the 18th century that distinctions are made between Navajos living among the four sacred mountains and Apaches living to the north and east of Taos and the Spanish settlements.

At the beginning of Spanish contact, no tribes had horses, sheep or domesticated animals other than dogs. From 1540 until 1680 nomadic tribes warily watched Spanish soldiers and priests force their will upon the Pueblo peoples. Then, with the successful Pueblo revolt of 1680, everything changed for Indians in the West. The Pueblos made little use of horses and sought to kill them during the revolt, but the Utes and Navajos felt otherwise and minor horse stealing prior to 1680 increased to major theft after the Spanish had been forced to retreat all the way south to El Paso. The Utes, who had been primarily involved in the deer trade by bringing prime finished buckskin into the trade fairs at Abiquiu and Taos, saw the opportunity to become rich with horses as did the Navajo. Major horse herds were acquired by both tribes, as well as churro sheep herds for Navajo weavers. Utes traded horses far to the north, and in northern Wyoming and southern Montana they received a valuable trade item they could never barter for with the Spanish—guns traded across the Great Lakes by the British. Guns were also acquired from tribes to the east and French trappers and traders.

By the 1740s the entire Southwest was re-made by the swift and deadly combination of armed Native American raiders on horseback. The territorial boundaries for the historic tribes became more distinct with Apaches to the east of the Rio Grande and south into southwest New Mexico; Navajos within their Four Sacred Mountains, and Utes ranging across all of Colorado and onto the Great Plains to hunt buffalo. No longer confined to the mountains, Utes could now travel far and wide to hunt, and they began to adopt the material culture of leather shirts, leggings, teepees, and parfleches similar to the Plains tribes.

The Gobernador area of northwest New Mexico may have been especially important for the Navajo clans as they moved into the Four Corners. This area seems to have served as a “cultural hearth” and an origin place for many songs, chants, and ceremonies. In addition there is the architectural enigma of the “pueblitos” or tiny pueblos that dot the mesa tops and are built close to ancient male forked-stick hogans. Whatever the Athabascan people learned in the gobernador area, it helped solidify them as distinctly Navajo, though certain chants and ceremonies also seem to reflect Pueblo traditions. Intriguing ceremonial rock art suggests both Navajo and Pueblo influence.

The northern boundary for the Spanish frontier was the genizaro community of Abiquiu, which was constantly raided by Utes, Apaches, and Navajos. As the slave trade increased on the Old Spanish Trail, women and children were taken captives and brought east to Taos and Santa Fe or west to Los Angeles. The Paiutes so feared that their children would be taken as slaves by Ute war parties that they insisted on reservation lands to the north of Salt Lake City and well off the Spanish Trail. By the first decades of the 19th century Taos Pueblo had been rebuilt with few doors and entrances, and exits only by roof hatches, which could be secured when raiders came near. Ute oral traditions recount “cannibal” stories that may reflect family fears about losing children along mountain trails. Navajo oral stories also describe the slave trade, and one vivid story depicts the plight of a young girl, taken by Ute raiders, who escaped by stealing two horses. She rode so hard and fast to the south that one horse died beneath her. She cut the saddle off the horse, hung it in a tree, and rode on with the second horse until it died. Finally she walked and ran to safety. Three decades ago, in the same canyons where tradition says the story took place, an old cottonwood frame Ute saddle was found in a pinyon-juniper tree. The saddle is now in the Wheelright Museum in Santa Fe. Navajos believe the saddle is proof of the oral tradition.

Case Study: Hesperus Mountain or Dibe’nsta

Hesperus Peak in the La Plata Mountains is one of the four sacred mountains in Navajo cosmology and represents the northwest boundary of the Navajo cultural area. In 1868 when the Navajos were still incarcerated at Bosque Redondo, the chief Barbacito said they would do anything if only they could go home and not be sent to Oklahoma. In his speech to General Sherman he described the boundary areas including Hesperus Peak as one of the Four Sacred Mountains.

Hesperus Peak figures in Navajo lore not only from the treaty’s nineteenth century date but also much earlier in Navajo myth and legend. One of the most important of all Navajo ceremonies, the Yei Bi Chai or Nightway Ceremony is performed only certain times of the year and is one of two major healing ceremonies held only during the winter months when the snakes are hibernating and there is no danger of lightning. This ceremony is performed for eight days and nine nights and is initiated when a patient first seeks the help of a hand trembler, who can sense and feel symptoms of a certain nature.

By mid-afternoon of the second day of the ceremony sand is used to make figures on the four sacred mountains and the sand is placed in all directions beginning with the east, south, west and finally the north. Talking God enters the hogan where the ceremony is being performed and he rotates himself around the patient four times in a clockwise motion beginning with the east and finishing in the north.

To this day Navajo medicine men, especially from Shiprock, New Mexico go to the area near Mt. Hesperus to gather sacred dirt and special plants for their medicine bundles. The heart and soul of the Navajo start with the four sacred mountains. Navajo medicine man George Blueeyes explains, “These mountains and the land between them are the only things that keep us strong…. We carry soil from the sacred mountains in a prayer bundle that we call dah nidiilyeeh. Because of this bundle, we gain possessions and things of value turquoise, necklaces, and bracelets. With this we speak, with this we pray. This is where the prayers begin.”

First Man and First Woman built the sacred mountains of the present Navajo land. According to author Raymond Locke, “They made them all of earth which they had brought from similar mountains in the Fourth World.” The sacred mountain of the north was named Dibentsaa or Mount Hesperus. Shonto Begay recalls a part of the Navajo creation story often told around the fire of his hogan. He explains, “The hero twins . . . were born for their mother Changing Woman, and their father, the sun . . . Monsters of great size and power roamed the land making life miserable . . . the hero twins were to save the people . . . in a great battle mountain ranges fell, lakes dried up and the earth trembled. One by one, the great giants were felled. After the people of the Fourth World were saved . . . they were given the four sacred mountains as guardians of our holy land, Dine tali.”

According to legend, the sacred mountains were the pillars that held up the sky and so as pillars they had to be fastened down. The sacred north mountain, or Hesperus, was tied down with a rainbow, black beads, mist, and many plants and animals were added. A dish of black beads, paszini, held two blackbird eggs under a cover of darkness, and on Dibentsaa lived Pollen Boy and Grasshopper Girl. Because of the sacred nature of Hesperus, “sacred mountains should not be climbed unless it is done in a proper way through prayer and song, and they should be returned to by medicine men every twelve years to renew their Blessingway prayers,” wrote Robert S. McPherson.

Peggy Beck, Anna L. Waters and Nia Francisco in The Sacred: Ways of Knowledge, Sources of Life explain, “There were four Holy Boys. These beings First Man called to him. He told the White Bead Boy to enter the Mountain of the East, Sisnajini (Blanca Peak in the San Luis Valley of south central Colorado). The Turquoise boy he told to go into the mountain of the South, Tsodzil (Mt. Taylor near Grants, New Mexico). The Abalone Shell Boy entered the mountain of the West, Dook’oslid (San Francisco Peaks near Flagstaff, Arizona). And in the Mountain of the North, Dibe’nsta (La Plata Mountains near Durango) went Jet Boy.”

The authors explain that the Holy Beings “fastened the mountain of the North, Dibe’nsta, to the earth with a rainbow. Over it they spread a blanket of darkness. They decorated it with bash’zhini, obsidian, black vapors, and different plants and animals. The lightning was sent to guard the Jet Boy’s doorway to the north.” Part of the sacred nature of Mt. Hesperus comes from the sacred nature of all four of the Navajo boundary mountains. They are visited by medicine men because “all the sacred mountains have their prayers and chants which are called Dressing the Mountains. All the corner posts have their prayers and chants, as have the stars and markings in the sky and on the earth. It is their custom to keep the sky and the earth and the day and the night beautiful. The belief is that if this is done, living among the people of earth will be good.” This knowledge is learned and practiced among the Navajo to maintain hozho or beauty.

Hesperus Peak is also known as “Big Sheep Mountain” because it was “made of sheep—both rams and ewes.” The Holy Beings provided riches in the form of livestock so herders petitioned Big Sheep Mountain for assistance to grow and bless their herds. Navajos believe “The mountains were put here for our continuing existence . . . All of the living creatures, like sheep, horses, cows, etc. said we will help with furthering man’s existence.”

The soil Navajos gather at Hesperus Peak, or dzillezh, is brought home to protect families and livestock. Blessing animals with prayers and special soil brings rain and more animals to the herds. An elder explained, “livestock is what life is about, so people ask for this blessing through dzillezh. From the sheep and cattle, life renews itself. Who would give birth in a dry place? This does not happen. You get many lambs and calves from the plants around here. On the tip of these plants are horses, cattle, and sheep. They are made of plants which are sheep.” Just as in accounts described in the book The Ecological Indian, the belief that there is a relationship among spirits, livestock, and plants is not unique to the Navajo. Authors Aton and McPherson add, “Navajo expansion north (of the San Juan River) and the use of natural resources were based in religious faith not scientific practice. For this reason, Navajos believed the more sheep there were, the more rain and plants would be available to feed them.” Hence, the religious aspect of Hesperus Peak takes on even deeper meaning.