Mountain Men and Miners

Mountain Men and Miners

by Norm Vance

To set the scene for the European explorers’ first full-scale move into the San Juan, we must understand a few things. First, the San Juan and other places in the mountains were entered later than the lower lands. As man first traveled into these rugged mountains, they reported the rough terrain and the long, cold winters.

The early Spanish explorers that crossed the San Juan are outlined in accompanying articles on this website. Here we discuss not the first explorers, but the first white men to live and work in the San Juan: the trappers or “mountain men.” These were certainly a hardy group of men. They faced the San Juan with no roads and no maps. The Indian population was a constant danger, and even a simple accident could mean sure death. Only Indian hunting trails existed, and a man could only take along as much supply as a few horses or mules could carry. There were no wagon roads yet. The early mountain men had to face danger and death daily. They had to be able to consistently find and kill animals for food, and to insure they did not fall prey to bears or lions and become food themselves. They learned to survive by harvesting naturally growing food from friendly Indians.

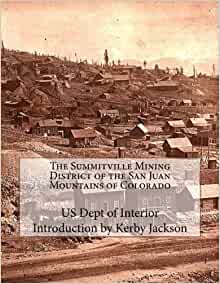

The Summit site on the Continental Divide northeast of Pagosa Springs. There is good access in summer months.`

The early mountain men were drawn into the San Juan in search of beaver and wildlife pelts. There was an active market for the pelts in the United States, in England and in Europe. The refined gentleman of the day developed a fashion trend of beaver fur on his coat lapel and also on winter hats; so this style created a “pelt rush” to satisfy the need.

Their life was not only harsh but also lonely. It was not a life for Anglo women. Fortunately, the trapper seemed to be the loner type. It has been said that these trappers were simply people who moved toward this type of life because they couldn’t get along in society.

A photo of the little town in its prime, not much is it?

They worked hard and often, wearing the same clothes for months on end. The mountain men came from all over Europe and the rest of the world. When they came across each other on a trail, there was a good chance that they could not communicate!

Joseph Williams, a Methodist preacher, entered an encampment and recorded a firsthand view of the mountain men. He said that this camp was as wicked as any place he had ever seen. They were dirty and greasy, and his overall impression was poor; “They bought, sold, and gambled for Indian women, drank and swore continuously and fought each other without reason or notice.” Preacher Williams tried to save these evil men, but none would respond!

In the 1840s the fur business fell upon poor times. The “fur rush” was over forever. Also gone forever were the original mountain men, and the unexplored mountains he worked and lived in.

Some mountain men reported back to the “States” on the beauty and vast awesomeness of the Rockies. It was these reports that drew continued interest from the civilized world to the east. John Charles Freemont was an early “pathfinder,” sent by the government to forge a trail west through the San Juan. Mrs. Freemont’s books on his expeditions became popular reading. Freemont was inspired and guided by mountain men but failed several times. On one expedition he became stranded by an early snowstorm in the area just northeast of Pagosa Country. His men suffered greatly and had to eat their horses, mules, and each other to survive.

The government wanted and needed an easy trail to California. There were known passageways in other areas, but none across the southern Rockies in Colorado and New Mexico. The Grand Canyon made travel west of New Mexico impossible, so a route across the San Juan and north of the canyon was important.