It is important for all Pagosans and those interested in Pagosa and its history to remember some of the more fascinating events in the past. It is good to recall that the Pagosa area was late being settled because of the harsh landscape. The mountains pushed explorers and settlers moving west to the south where travel was easier. Finally, the lust for riches in gold brought prospectors and miners to the area when other California and Colorado mining districts became depleted or over crowded. The California and big Colorado gold rushes were over before Pagosa was settled. The following is an early history of the Wheeler Expedition of 1874. Norm Vance, editor.

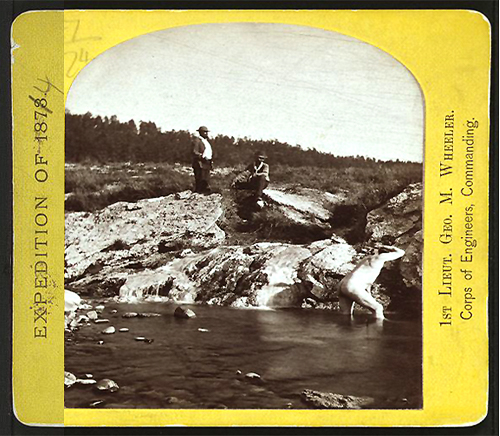

In 1874 Timothy O’Sullivan traveled the west with the Wheeler Expedition. He traveled with early photographic equipment and recorded these photos of the Pagosa Hot Spring. This early photograph is likely the first of a person soaking in the waters. This must be an older vent no longer in existance as it appears smaller and shallower than “The Mother Spring.” There is no doubt the surface around the Mother Spring has been altered several times over the years and history tells us at one time there were many vents perking the water.

This photo is labeled 1874. Sullivan was in Pagosa two years before the first settler, Welch Nossaman, made his treck down the East Fork from Summitville and built the first cabin near the spring.

This fellow seems to be testing the waters.

Sullivan climbed up the side of Reservoir Hill to get this photo looking west.

Timothy H. O’Sullivan (c. 1840 – January 14, 1882) was a photographer widely known for his work related to the American Civil War and the Western United States.

Timothy H. O’Sullivan with imprint of F.G. Ludlow, Carson City, Nevada Territory on verso. Taken between 1871-74 while O’Sullivan was the official photographer for the Wheeler Expedition.

O’Sullivan was born in Ireland and came to New York City two years later with his parents. As a teenager, he was employed by Mathew Brady. When the Civil War began in early 1861, he was commissioned a first lieutenant in the Union Army.

After being honorably discharged, he rejoined Brady’s team. In July 1862, O’Sullivan followed the campaign of Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Northern Virginia Campaign. By joining Alexander Gardner’s studio, he had his forty-four photographs published in the first Civil War photographs collection, Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War. In July 1863, he created his most famous photograph, “The Harvest of Death,” depicting dead soldiers from the Battle of Gettysburg. He took many other photographs documenting the battle, including “Dead Confederate sharpshooter at foot of Little Round Top”, “Field where General Reynolds fell”, “View in wheatfield opposite our extreme left”, “Confederate dead gathered for burial at the southwestern edge of the Rose woods”, “Bodies of Federal soldiers near the McPherson woods”, “Slaughter pen”, and others.

More proof of this not being the Mother Spring is that no one can sit in the water directly from the earth. This may not be a vent, but a low spot the water drains into cooling as it flows across the ground. There was a pool with a 100 foot cooling stream to it as late as the late 1980′s.

In 1864, following Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s trail, he photographed the Siege of Petersburg before briefly heading to North Carolina to document the siege of Fort Fisher. That brought him to the Appomattox Court House, the site of Robert E. Lee’s surrender in April 1865.

From 1867 to 1869, he was official photographer on the United States Geological Exploration of the Fortieth Parallel under Clarence King. The expedition began at Virginia City, Nevada, where he photographed the mines, and worked eastward. His job was to photograph the West to attract settlers. O’Sullivan’s pictures were among the first to record the prehistoric ruins, Navajo weavers, and pueblo villages of the Southwest. In contrast to the Asian and Eastern landscape fronts, the subject matter he focused on was a new concept. It involved taking pictures of nature as an untamed, pre-industrialized land without the use of landscape painting conventions. O’Sullivan combined science and art, making exact records of extraordinary beauty.

This photo shows a large mound of mineral deposits in the distance. That may be the location of the pool in the other photos. Notice the complete lack of signs of human activity.

In 1870 he joined a survey team in Panama to survey for a canal across the isthmus. From 1871 to 1874 he returned to the southwestern United States to join Lt. George M. Wheeler’s survey west of the 100th meridian west. He faced starvation on the Colorado River when some of the expedition’s boats capsized; few of the 300 negatives he took survived the trip back East.[citation needed] He spent the last years of his short life in Washington, D.C., as official photographer for the U.S. Geological Survey and the Treasury Department.

O’Sullivan died in Staten Island of tuberculosis at age 42.