The following text Courtesy of Center of Southwest Studies,

Fort Lewis College

The Center of Southwest Studies, Fort Lewis College

TCP=Traditional Cultural Properties

RAILROADS

Following the removal of Ute Indians to reservations in 1881, the San Juan Mountains became an important location for mining, smelting, logging, commerce, and urban services, but the economic success of these enterprises depended on the development of rail transportation.

Equipment, supplies, merchandise, whiskey, and passengers were carried into the mountains, and ore, lumber, coal, livestock, and passengers were carried out. Because of the rugged terrain of the San Juan Mountains, the railroads built in this area usually required innovative engineering. All were narrow-gauge lines, commonly with steep gradients and tight curves. Although in some instances grades could follow, in part, the valleys carved by streams, round-about routes were required when a more direct line was impossible. I n addition to railroad corporations, some mines also operated tramways, and rails with freight cars connected to railroads.

Toll roads and railroads were essential to the survival of the isolated mining towns. Entrepreneur Otto Mears built so many of the transportation routes in southwestern Colorado that he is known as the “Pathfinder of the San Juans.” Mears is responsible for many routes, including:

Silverton to Ouray toll road (Million Dollar Highway)

Dallas-San Miguel-Rico toll road (partly the Dallas divide road)

Silverton-Animas Forks-Mineral Point toll road

Rio Grande Southern Railroad

Silverton Railroad

Silverton, Gladstone and Northerly Railroad

Silverton Northern Railroad

Mears’ roads’, and his spectacular engineering feats shaped Southwest Colorado. His work, alone, should be considered as a Multiple Property Listing on the National Register of Historic Places.

Even as toll roads were developed in the 1870s, the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad contemplated the best route to connect to the mineral rich San Juans. By 1881 the railroad had extended west from Alamosa to Durango, and was on its way to Silverton. The Rio Grande Southern was built to connect the western San Juans’ mining wealth to the existing Denver and Rio Grande Railroads at Ridgway and Durango. Since the RGS covered some of the most remote and rugged country in Colorado, the railroad also served as the only means for mail delivery and passenger travel. People in Rico boarded the train, for instance, to travel to their dentist, with plans to return the same day. Much of the highway that replaced the route of the RGS was not paved until the 1960s. The Rio Grande Southern reached Durango in 1893, and the route came from the west –Mancos.

The railroads had great impacts on the establishment and physical development of communities in the region. The town of Big Bend was located a few miles away from the proposed route of the Rio Grande Southern railroad; it was abandoned in favor of a new town along the route of the railroad named Dolores. Pagosa Springs suffered from a poor quality railroad spur connection to the main line of the Denver and Rio Grande, and never fully benefited from the railroad. Animas City soon faced obscurity as the Denver and Rio Grande built its own town of Durango located just a few miles to the south. It appears with the passage of time that Silverton ultimately won the location battle with the railroad. The depot is now in a deserted section of town and the train actually passes the depot to load and unload passengers in central Silverton.

The railroads also eased the development of a broader based economy, beyond the booms and busts of precious metal mining. Farmers and ranchers could capitalize on railroad freight rates to ship their produce and livestock. The railroads also brought goods and other elements of civilized society, such as teachers and clergy people. Communities with access to the railroad thrived, while the more isolated mining towns slowly withered.

The mountain climate created hazardous conditions, with long, cold winters bringing heavy snow and snowslides that frequently blocked routes, while the short summers might bring heavy rains and flash floods that brought mudslides and washouts. Railroad workers required unusual stamina. They were hard workers, or else they were fired or quit. They represented a variety of nationalities and races, including some Navajo construction workers. Hispanic men were in the majority among construction crews and gandy dancers (section crews). Yard workers came from various backgrounds, as did crews on trains, consisting of a hierarchy of conductors, engineers, brakemen, and firemen. Managers lived in nearby rail centers like Durango and Silverton, while owners lived in distant cities, with the exception of an individual like Otto Mears and lumber company men.

Many railroad rights-of-way have disappeared, but not the original Denver and Rio Grande. By an act of Congress, the Denver and Rio Grande Railway Corporation received its right-of-way as well as lands needed for depots, yards, shops, and other necessary facilities for the railroad’s operation. Because many of these railroads, their facilities, and associated towns occupied lands owned by or promoted by the railroads themselves, few of these properties are on public lands today, exceptions being small railroads that were abandoned, especially those serving lumber camps.

Lumber was cut and hauled in vast amounts. One legend is of a train full of aspen leaving Pagosa Country for Japan to make chop sticks!

Lumber was cut and hauled in vast amounts. One legend is of a train full of aspen leaving Pagosa Country for Japan to make chop sticks!

I. Railroads associated with mining and smelting of metals

A. Denver and Rio Grande Western Railroad (1881-1968)

As the San Juan Extension was being constructed around the southern end of the San Juan Mountains in 1881 from Antonito, Colorado, the railroad each month was bringing hundreds of laborers to work on grading crews. As John B. Norwood has described labor problems, “Apparently most of the recruits deserted to the mines, returned home or continued to other parts.” The contractor said, “Our expense in this line clearly demonstrated that the class of labor secured was the least desirable. Any number of worthless fellows were anxious to get a free ride to Colorado.” Norwood continued, “Out of this problem of recruiting labor grew an important decision: The Rio Grande began recruiting local help, which meant the brown, lean and ever-enduring Nuevo Mejicano. Indeed as the Rio Grande headed toward Santa Fe and the San Juan, it was advancing into the heart of the New Mexican country and culture. From that time forward, the Nuevo Mejicano would assume a dominant role in the building of, and later, the maintenance of the roadway and tracks of the narrow gauge.”

In 1881, the San Juan Extension of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad reached the railroad’s own new town of Durango, just short of the existing town of Animas City, and quickly became the main shipping point and commercial center in the San Juan Basin. The railroad had a station, shops, roundhouse, yards, and other facilities that brought a large number of railroad employees to the area, many being Hispanic. Service on the San Juan Extension through Durango continued south to Farmington, New Mexico, on its Farmington Branch until 1968. The Silverton Branch [see below] continued as an excursion line.

The D&RG’s Silverton Branch, built in 1882 through Animas Canyon to Baker’s Park, where Silverton became the center for rail operations served silver and gold mines and smelters in the area. Construction of this branch required cutting a roadbed along a sheer rock cliff, called the High Line, above the Animas River where the gorge was too narrow to accommodate it. Frequent avalanches in the valley caused a snow shed to be built four miles south of Silverton. Three other narrow-gauge lines, owned by other companies, became feeders into the Silverton Branch at Silverton. After World War II Colorado and, with it, the San Juan region, changed rapidly, as population and tourism increased. When the D&RGW proposed to abandon its San Juan Extension in the 1950s, public clamor led to the ICC’s denial of the abandonment request. The D&RGW continued to operate the line, mostly for tourists, while pursuing abandonment of the line from Durango east to Antonito. The D&RGW succeeded in their efforts and made its last run between Durango and Antonito in 1968. The states of Colorado and New Mexico joined in the purchase of the Chama to Antonito route and developed the line as a tourist ride. Meanwhile the D&RGW had purchased a number of the buildings located around the Durango Depot with initial plans to develop the area as a tourist destination. The project broke down, the railroad leveled a number of the historic buildings it had purchased, and eventually the railroad sold the property to an out of town developer. The Durango-Silverton route was sold to Charles Bradshaw in 1981. Mr. Bradshaw succeeded, in 1988, in having the popular excursion route exempted from the oversight of the ICC, by successfully arguing that the train no longer carried any valuable freight other than tourists. The line was sold to another operator in the 1990s and continues to be a popular tourist attraction. It continues to provide the only mechanized access point, at Needleton Tank, for hikers visiting the remote Needles and Grenadier Mountains.

B. Rio Grande Southern Railroad (1890-1960)

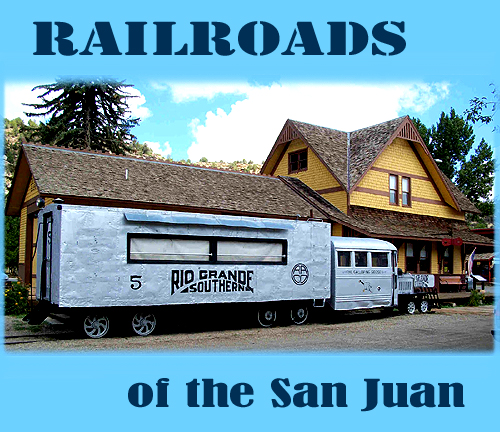

A narrow-gauge line built by Otto Mears and investors in Denver, the Rio Grande Southern Railroad served the western area of the San Juans, with its circuitous route passing through Telluride, Ophir, Lizard Head Pass, Rico, Dolores, and Hesperus. This route was necessitated by the rugged terrain of the mountains and Uncompahgre Gorge, and it advantageously served important mining areas, lumber operations, and a coal mine. Its operation was dependent on connections with the D&RG on the north at Ridgway and on the south at Durango. It reached Rico in 1891, thereby eliminating most traffic on the former Rockwood and Rico Wagon Road, and it reached Durango from the west in 1893. The line was abandoned in 1951. Its trains carried freight and passengers, usually with a mixed train. Between 1931 and abandonment, the line’s seven Galloping Geese provided passenger and mail service with cars built with automobile engines and rail wheels. Treasured by nostalgic rail fans today, they were important to the way of life of local people and businesses along the line during the Depression and World War II. Galloping Goose No. 5, restored and operational, is kept at Dolores, while five others still exist elsewhere. Several short lines connected lumber camps and mines to the Rio Grande Southern. A spur of the RGS operated at Parrott (Mayday) from 1906 to 1926. The spur began west of Hesperus.

C. Silverton Railroad (1887-1924), also called the Red Mountain and Silverton Railroad

Otto Mears built the twelve-mile-long Silverton Railroad north from Silverton to Albany (near Ironton) by way of Mineral Creek, Chattanooga, and Red Mountain with some short spurs. The original hope of investors was to connect Silverton and Ouray, but beyond Albany, located in Red Mountain Park, there remained an impassable gap of six miles to Ouray which forced the indefatigable Mears to construct the circuitous Rio Grande Southern Railroad.

D. Silverton, Gladstone, and Northern [sometimes Northerly] Railroad (1899-c.1915)

This railroad along Cement Creek connected the Gladstone Mine to Silverton. It had a never–achieved goal of reaching Lake City, too. Built by owners of the Gladstone Mine, Otto Mears leased this railroad from 1910 until he bought it in 1915 and then abandoned operations soon after the purchase.

E. Silverton Northern Railroad ( 1895-1942)

The Silverton Northern Railroad was built by Otto Mears from Silverton to Eureka, nine miles, in 1896 with an additional Green Mountain Branch, 1.3 miles, built in 1905. Mears also added a short spur into Cunningham Gulch. The Green Mountain Branch was removed in 1920, while the rest of the line closed in 1939. Such extensions and removals reflected the current economics of mining.

II. Railroads associated with coal mining

A. Perins Peak Railway (1901-1926)

The five-mile, winding Perins Peak Railway was built in 1901 by the Boston Coal and Fuel Company up Lightner Creek to connect the Boston Coal Mine at Perins Peak to the Rio Grande Southern Railroad at Franklin Junction, two miles west of Durango. The railroad was sold to a subsidiary of the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad. The D&RG leased the railroad to the RGS. The line was abandoned in 1926.

Loading ore was done with simple convayor belts and structures.

III. Railroads associated with lumber operations

While railroads were being constructed, timber was cut and milled along the grades until the supply dwindled and spurs were built by lumber companies to access stands of trees. Wood was used for railroad ties and for mine timbers, as well as for construction of buildings and for fuel. In many places, logs were skidded down to sawmills and rails. Names of some of these operations changed from time to time, as did locations. Rails, mills, boilers, saws, and shacks were moved from one location to another when an area became denuded and new camps were set up in another part of the forest, leaving behind little more than a pile of sawdust. After the San Juan Forest Reserve (1903) and, next, the San Juan National Forest (1905) were created, the lumber industry dropped off drastically, and the common practice ended of setting up new camps served by spurs. Grades of many of these railroads have vanished from sight.

A. Rio Grande, Pagosa and Northern Railway (1899-1936)

Among several rail branches and spurs built north and south of the Denver and Rio Grande, was the Rio Grande, Pagosa and Northern Railway, built northward from Pagosa Junction to Pagosa Springs in 1899-1900. The line was built by the Pagosa Lumber Company under an agreement with the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad to eventually turn the line over to the D&RG. It carried lumber and sometimes other freight, sheep, mail, and passenger trains to and from Pagosa Springs. In 1906 the line became the D&RG Pagosa Springs Branch of the D&RG Railroad, which operated the line until the Depression hit. During its peak, three branches continued northward from Pagosa Springs.

B. Pagosa Lumber Company Railroad (1906-1916)

The Pagosa Lumber Company operated this subsidiary, running south along the San Juan River from a point west of Pagosa Springs. It had more than fifty miles of lumber spurs.

C. Dolores area lumber company railroads

This area had several lumber operations with railroads operated by lumber companies. Two were operated by the Montezuma Lumber Company in the area around Dolores and east of Norwood. One of these went to Haycamp Mesa with several miles of spurs. It connected to the Rio Grande Southern Railroad at Glencoe. The second Montezuma Lumber Company operation succeeded the Colorado and Southwestern Railroad until about World War I. The Colorado and Southwestern Railroad Company had taken over the Dolores, Paradox and Grand Junction Railroad Company grade, which operated three lines north from Dolores between 1913 and 1925, with the Horse Camp (or Horse Creek Camp) being the center of its operations. It had more than fifty miles of track, including a line between McPhee and Dolores until 1948. The Rust’s Logging Railroad also served lumber companies between 1902 and 1906.

The material culture associated with the railroads is numerous and varied. The Fort Lewis College Office of Community Services has documented the remaining structures on the route of the Rio Grande Southern as part of the planning efforts for the San Juan Skyway. The Denver and Rio Grande route between Durango and Silverton now operates as a tourist ride, but the rolling stock is original (except for the diesel engines that are used in times of extremely high fire danger). The Durango-Silverton railroad, route and rolling stock are a national historic landmark (listed 1961). The Red Mountain Task Force has undertaken extensive cultural resource surveys in the mining district of the same name. The surveys have identified material culture related to both mining and the railroads. This survey work should be an important research resource. Volumes of material have been written about the railroads of the region and provide a good starting point in researching the railroads. The Center of Southwest Studies and the Animas Museum have oral histories of former railroad employees.

Automobiles and tourism have shaped many of the communities in the San Juan National Forest. Historic gas stations, auto courts and hotels are still to be found in most of these towns. Automobile travel brought more tourism, and affected the character of many communities with the introduction of automobile garages, gas stations, motels and restaurants that catered to travelers rather than to locals. Easier, more individualized transportation led to a recreation boom after World War II, resulting in new recreational facilities such as ski areas and additional campgrounds.

The less expensive transport afforded by truck travel led to demise of the railroads, but many communities still maintain ties to the railroad days. Dolores, for example, has resurrected the Galloping Goose, and built a replica of the old depot, while Mancos has built a visitor’s center in the style of its old depot.